Reports

The Forgotten War in Sudan: When Pain Meets Faith in Fate and Destiny

Sudan Events – Agencies

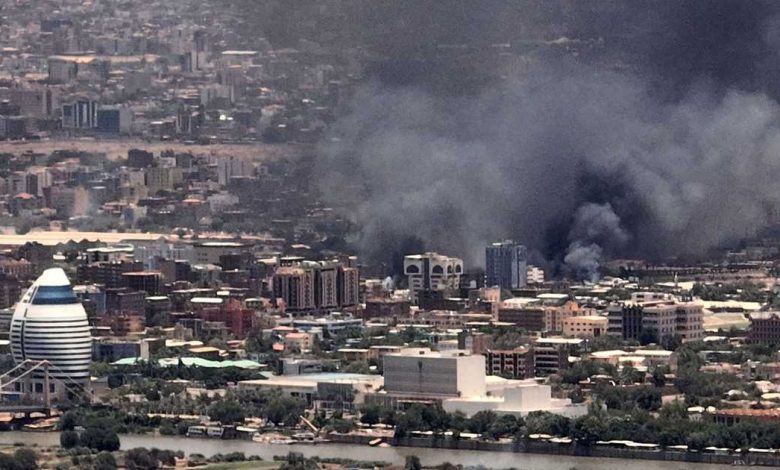

The British newspaper The Times published an extensive report from inside Sudan by its correspondent Anthony Loyd, shedding light on the ongoing conflict between the Sudanese army and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and its devastating effects on unarmed civilians.

The correspondent begins his report with a scene summarizing the tragedy of the forgotten war in Sudan: attending the burial ceremony of a man and a child in a single grave in Omdurman. This city, along with its twin sisters Khartoum and Bahri, forms the triangular capital of Sudan.

RSF Prisons

The man being mourned at Ahmed Sharfi Cemetery was Mohamed Abdelsalam, 37, nicknamed “Bunduq,” who worked as a builder.

Bunduq lived in the Al-Fatihab neighborhood, southwest of Omdurman, when the RSF took control of the area. He disappeared without a trace, only to be later found to have been detained by the RSF on suspicion of collaborating with the Sudanese Armed Forces. He was imprisoned in Soba Prison in Khartoum without his family’s knowledge.

In November, his sister Rania, 40, received a phone call from a man who told her he had found Bunduq lying on the roadside, emaciated and beaten, on the brink of death.

Rania rushed to rescue her brother, crossing 38 RSF checkpoints. When she finally found him, Bunduq was so frail and unrecognizable that he could not stand.

Rania recounted that Bunduq was unable to walk, so she transported him on a cart to a bus station and then home. There, Bunduq described a year of terror under RSF captivity, surviving on a single cup of lentils a day, enduring frequent beatings, and witnessing fellow prisoners die from starvation or torture.

Whenever his sister tried to feed him, he vomited due to severe malnutrition and possible internal injuries. His condition deteriorated further, and he passed away 10 days after being rescued, according to journalist Loyd.

On the Margins

The Times notes that torture and disease are not uncommon causes of death in Sudan, where bullets, shelling, forced starvation, looting, and rape are part of the war’s arsenal.

Thousands of victims have been buried across Sudan since the war began in April 2023. Many more have died from malnutrition in the desert, their fate undocumented and unknown.

Despite the severity of this crisis, which threatens millions of lives and risks turning Sudan into a failed state, the war has remained on the periphery of international attention, overshadowed by conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East.

A Crippled Medical Sector

Among Sudanese medical staff fighting to save lives, anger is mixed with a sense of abandonment by the world.

The newspaper quotes Dr. Gamal Al-Tayeb Mohamed, director of Al-Nau Hospital in Omdurman—one of the few remaining operational medical facilities in the war-torn city. Standing in a ward filled with injured patients, he remarked, “I don’t think the international community cares or even knows what’s happening here.”

He added, “They don’t realize the impact of this war on the poor and the vulnerable who’ve lost their livelihoods, jobs, and everything around them.”

According to The Times, the war has destroyed 60-70% of Sudan’s medical facilities, including most of the country’s pharmaceutical factories. The remaining facilities are under immense pressure. Al-Nau Hospital, for instance, receives 500 to 600 patients daily, many of whom are treated on the floor due to overcrowding.

Children of War

Dr. Mohamed bitterly asked, “Where is the World Health Organization and the Red Cross? We have never seen them here. Maybe they went to Port Sudan,” referring to the temporary seat of government. He noted that only Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) seems to be present.

After his conversation with Loyd, Dr. Mohamed tended to a six-year-old girl named Ghitha. The previous morning, while cleaning her teeth in the courtyard of her family’s home in Al-Qamayir neighborhood in Omdurman, an RSF-launched shell struck. Her nine-year-old brother, Mohamed, was playing nearby on his bicycle when the shell hit him in the head, killing him instantly and injuring Ghitha’s arm.

Ghitha now lies speechless, with shrapnel wounds in her left arm and leg. Her grandmother, who is caring for her, lamented, “The shell tore through our son before our eyes, and we could do nothing.”

The Notable Undertaker

Ironically, undertaker Abideen Derma, 60, has become one of the city’s most recognized figures. Drivers, pedestrians, and children wave to greet him, and some even stop to shake his hand. A billboard featuring his image in a distinctive green robe and faded turban has made him an emblem of the city, according to the report.

Loyd quoted Derma saying, “These days, with war, disease, and weakened immune systems due to stress and hunger, we bury 15 to 20 people daily, sometimes up to 50.”

The journalist recounted his walk along artillery-ravaged streets near the Sudanese Radio and Television headquarters. There, Sudanese Armed Forces soldiers pointed out makeshift graves, some partially dug up by stray dogs, where civilian victims were buried.

“It was unclear whether they had died from shelling or in RSF prisons. Bloodied clothing hung from nearby trees. On one grave, a cross made from branches and a torn woman’s dress marked the resting place of a Christian victim,” Loyd described.

A Written Fate

Loyd highlighted a phrase he encountered in Arabic: Maktoub, meaning “written fate.” It reflects a widespread sentiment among Sudanese people that what befalls them is preordained, offering a bittersweet sense of acceptance despite the harsh reality.

This acceptance, Loyd observed, may stem from faith or the grim realization that without hope, endurance becomes the only option. The catastrophic war has claimed 150,000 lives and displaced 11 million people, with no end in sight.