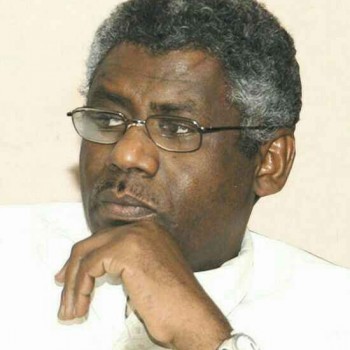

Al-Azraq… Where Is Your Smile? And How Were You Tamed?

As I See

By Adil El-Baz

1

How can memory laugh and cry at the same time? I’ve been torn ever since I heard the heartbreaking news. I tried, in vain, to convince myself it was false—because how could I ever write about Al-Azraq without laughing? And how can one laugh when their heart is shattered and their soul crushed by grief?

For over twenty years, I never once met him without our laughter preceding us. His smile always appeared first, revealing that signature gap between his teeth—a gap that seemed to cast a beautiful shadow over the horizon of laughter. Our meetings began not with greetings or pleasantries, but with mad laughter that carried us straight into stories, poetry, novels, and exquisite conversation.

The day I called him and we didn’t laugh, I knew Abdullah was bidding the world goodbye. Death had sunk its claws into his throat—the very place where his laughter was born, where the springs of his joyous chuckles gushed. What a cruel disease, to strike only the part of him that gave his life its deepest human meaning: the essence of who he was and the balm for every wound he carried.

2

A face of light has vanished. A towering figure in poetry and diplomacy has left us. A noble soul has passed on—a man who gave words their soul, values their shadow, and his country a melody of loyalty.

Abdullah Al-Azraq is gone: the poet, the writer, the diplomat. A diplomat whose laughter echoed with wisdom, who walked in Sudan’s footsteps like letters following meaning. A man of generosity and honor, whose words were always true and beautiful.

Al-Azraq—(do I really say “was”? Woe to me…)—was as multifaceted as the hues of a sunset sky. A poet weaving light into meaning, a literary craftsman handling language with the finesse of a sage. His presence lit up every gathering. In his absence now, sorrow lingers in the corners of hearts that loved him and drank deeply from his nobility.

He was unforgettable: noble-hearted, tender-spirited, principled, loyal in friendship, and authentic in every word and deed.

3

If you seek to know Abdullah Al-Azraq the diplomat—the elegant, courageous, sharp diplomat—read the reflections of his companions: Dardiri Mohamed Ahmed, his friend Muawiya Al-Toum, and his colleague Khalid Musa—may God bless their pens. They knew him as a statesman who wore silence with grace and measured words with the scale of wisdom.

4

To explore the power of his poetry, read his masterful verses, or consult the great poet and critic Ibrahim Al-Qurashi, or listen to the esteemed poet Khalid Fathalrahman speak about the originality of his voice and the richness of his vocabulary. After all, he was a descendant of the Majadhib—and what a lineage that is! A people of faith, generosity, honor, piety, and poetry—from Abdullah Al-Tayyib Al-Majzoub to Akir Al-Damer.

Read his poem Kaabat Al-Madhyoom:

“Oh, how I long to spend a night under the boughs of dignity,

To soothe my aching heart…

They are a people proud as the morning,

Their virtues surpassing all count…

Their shade glows with pride and grace,

Illuminated by knowledge and wisdom…”

Thirty-nine lines of classical Arabic verse in al-taweel meter—what a poem, what language, what a poet!

5

If you never knew him as a writer, look to his book “Managing Savagery”, or dive into the archives of Al-Ahdath newspaper, where his writing displayed rare brilliance and deep insight into global politics. Hundreds of articles reveal a writer of depth and wonder.

I remember reading a single piece of his in the Sudanese press and seeking him out, hoping he would write for Al-Ahdath. He agreed without hesitation, saying, “I have only one condition: that the article be published exactly as written.” I told him: “That’s how we do it at Al-Ahdath—we never touch our writers’ words.”

But now, allow me to tell you about Al-Azraq, the man.

6

I met Abdullah Al-Azraq the smiling human over two decades ago. One evening, as I wandered Oxford Road—my usual London pastime—someone suddenly pulled me into a warm embrace, laughing. I was taken aback, having no idea who this cheerful man was. Sensing my confusion, he said, “Shame on you, being in London and not visiting one of your writers?”

I looked closer. The face matched the memory. “You’re Ambassador Abdullah Al-Azraq!” What a meeting. I told him: “I have a story about embassies that I’ll share with you someday.”

That story goes like this: Despite all my travels, I’ve always avoided embassies and diplomats—whether I know them or not. After a few visits to Sudanese embassies abroad, I found that when you greet them with courtesy, their eyes bulge with suspicion, fear takes over, and they assume you’ve come to burden them with something. They greet you with the tips of their fingers, then vanish.

Since then, I stopped visiting Sudanese embassies altogether. Of course, there are exceptions—good people who welcome you and ease your loneliness—but they are few.

7

After that encounter on Oxford Road, Al-Azraq insisted on taking me home with him. Reluctantly, I went—and regretted only that I hadn’t known this man earlier. That meeting sparked a friendship that lasted more than twenty years. Every time I visited London, I found his home alive with guests, poetry, stories, and joyful company.

I still remember those evenings—he would read poems not meant for the public, while we listened to stories from Al-Sadiq Al-Raziqi, Majid Abdel Bari, Abdelrahman Suleiman, and many others, all of them deeply cultured and refined.

8

The only time I visited him and wasn’t greeted by his laughter was when he was in the hospital—after his car fell from the Shambat Bridge. Behind our tears, we hid our laughter, imagining him making jokes about himself and others. And indeed, the moment he regained consciousness and saw us, he said: “Are you here, or is this the afterlife?”

We laughed, and rejoiced, and knew he was well—so long as he could still laugh.

9

When he left the hospital, it was a day of great celebration. I’d never seen so many people visit a recovering patient. They came by the dozens—from neighbors, close friends, diplomats, to delegations from his Majzoub family and from every faction and party.

I imagined: had Abdullah Al-Azraq been buried in Khartoum, no road or cemetery could have held the crowds. But fate had it that he would be laid to rest far from the land he loved, the land he adored, where he wrote his finest poetry and lived his most beautiful days.

10

When Al-Azraq used to write for Al-Ahdath, he never accepted payment—like many of our writers then, whose generosity flowed like water.

Each month, he’d instruct: “Pay so-and-so this month—he’s raising orphans. Pay that one—he’s burdened. Another—his expenses are high. Our old uncle—he’s ill.” He didn’t stop there. He sent money to friends and colleagues, especially journalists, always checking on their welfare.

11

In London, he extended his hand even to opposition figures and strangers—some of whom later attacked him. Still, he never complained, never responded. He’d tell me: “Let them. One day, the truth will be known.”

He endured much, for to speak would be to expose secrets of the state entrusted to him. So, he bore it all, waiting patiently for his reward—on the Day the unseen will be revealed, and truths known.

12

O you who dwell in the nation’s memory—how did you slip from our breath, leaving your final word suspended between the line and the tear?

O you who departed in the silence of sages, nestled in the folds of poetry, now (God willing) wrapped in silk and brocade, resting on plush cushions beneath shaded groves and clustered banana trees…

Tell me—O blue-eyed, white-hearted one, always laughing—how were you tamed? And where is your smile now?

Sleep peacefully, you who are now free of life’s weariness. Rest amid your pages and your memory. Your name will live on the lips of all who knew you, laughed with you, and cherished your warmth.

As long as the flag of poetry flutters, and as long as our Nile sings of noble souls—your name will remain.

May God have vast mercy on you, grant you Paradise and eternal peace, and bless your family and loved ones with patience and comfort.