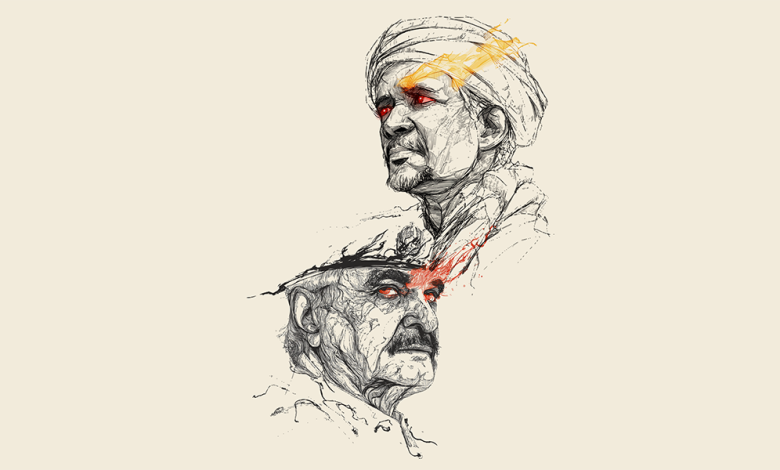

Haftar and Hemedti: Patriots or pawns in Trans-Saharan business interests?

Musab Mohamed Ali Hassan Alnaser

Sudan’s western frontier has become a tinderbox, where overlapping regional agendas are no longer negotiated in diplomatic backrooms but played out with bullets, gold, and tangled loyalties. At the centre of this volatile tableau stands the unspoken alliance between Rapid Support Forces (RSF) commander Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemedti, and eastern Libya’s militia leader Khalifa Haftar. Both men emerged from the margins of political geography, each determined to extend his influence across two neighbouring states teetering on the brink of collapse.

Here, we map the strands of their cross-border partnership through the so-called Border Triangle, a once-overlooked sandy domain now transformed into a regional battleground stretching from Darfur to Benghazi. Long relegated to a cartographic footnote between Sudan, Libya, and Egypt, the Triangle has, since war erupted in Sudan, morphed into a strategic flashpoint and a perilous corridor for arms, fighters, and gold. The territory lies south of Egypt’s Siwa Oasis, west of Al Uwaynat, and north-west of Sudan. It now hosts multiple armed networks.

Meeting at El Alamein: A stormy diplomatic confrontation

In late June 2025, the Egyptian city of El Alamein became the stage for a heated diplomatic showdown when Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan sat down with President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, just as Khalifa Haftar and his son Saddam arrived on an officially announced visit. Though media images conveyed separate discussions, intelligence contacts and a Middle East Eye exposé reveal that the summit served as a covert face-off between Burhan and Haftar.

A senior Sudanese sovereign source told Atar that Burhan pressed al-Sisi on the north-western border dossier, presenting documents he claimed proved Haftar’s military and logistical backing for Hemedti’s RSF. A Sudanese intelligence informant, speaking to Middle East Eye, described a network smuggling weapons and drones through southern Libya, with transit facilitated from the Maatan al-Sarra base in Kufra. Burhan also recounted a previous Khartoum visit by Haftar’s son, Sadiq, who met Hemedti and donated $2 million to Al Merrikh Sporting Club.

That meeting reportedly escalated into a sharp confrontation after Burhan accused Haftar of funnelling arms from southern Libya into Darfur and alleged coordination with the United Arab Emirates (UAE), citing leaks that Maatan al-Sarra served as a military supply waypoint. Haftar vehemently denied all allegations, but Burhan insisted he possessed concrete proof. Egypt’s official posture remained muted, though al-Sisi is said to have bristled at the encounter’s intensity.

June 2025 shifts

In June 2025, the RSF declared full control of the Border Triangle after the SAF and its allied units withdrew. The SAF characterised the pullback as a defensive measure to repel aggression, accusing the RSF of coordinating an attack on its frontier posts with direct backing from Haftar-aligned Libyan forces, specifically the Salafi Brigade. In response, the Foreign Ministry loyal to General Haftar denied any involvement, dismissing the accusations as an effort to export Sudan’s crisis.

An RSF insider said that securing the Triangle was part of a military tactic aimed at opening new supply lines and recalibrating relations with Egypt, particularly following Hemedti’s speech, which hinted at possible dialogue with Cairo.

RSF control of this remote region has raised serious questions about the value of this stretch of desert, located south of Egypt’s Siwa Oasis, west of Al Uwaynat, and north-west of Sudan. Though barren, its geography positions it as a vital juncture among three nations and a strategic corridor for desert routes, smuggling, and irregular migration. It is also believed to contain untapped mineral deposits, notably gold, adding an economic dimension to its significance.

Military and economic importance

A senior general staff officer from the SAF told Atar that the area serves as a primary defence line against incursions from the west or north-west. It is used to establish observation and reconnaissance posts and to logistically monitor the movements of armed groups amid fragile security in Darfur and western Sudan.

Conversely, the RSF views the Triangle as a strategic opportunity to open alternative supply channels through Libya and even to the Mediterranean Sea. A source within Sudan’s National Intelligence and Security Service in Northern State said that the Triangle’s proximity to the North Darfur gold mines makes it an ideal launch point for extraction and smuggling, providing a key funding source. The area could evolve into a permanent logistical base and sphere of influence should conflict with the regular army persist.

For Egypt, the presence of irregular forces in the Triangle poses a direct threat to national security, especially as human and arms trafficking across its western border intensifies. Moreover, Haftar-aligned troops, backed by regional actors such as the UAE, whose political demands Cairo finds hard to reject, place Egypt in a bind between its traditional support for Sudan’s army and its intricate Libyan policy. Although an Egyptian security official told Atar that RSF control amounted to little more than a “moral victory”, recent Egyptian military movements near Al Uwaynat suggest preparations to counter any unexpected developments.

Military bases and Haftar’s support

Military installations surrounding the Border Triangle play a pivotal role in this struggle. On Sudan’s side, the Shafrilet base, recaptured by the SAF in April 2023, stands out as a key stronghold. The army has used it as a launch point for operations in the region, even as recent reports claimed that the RSF had retaken it.

On the Libyan front, multiple accounts indicate that Haftar’s forces rely on south-eastern bases, such as the Tamanhant facility, to provide logistical backing for RSF units. Moreover, intelligence support reportedly pours in from regional patrons, smoothing coordination between Hemedti’s fighters and their Libyan allies.

Haftar himself is accused of facilitating the transfer of munitions, drones, and mercenaries from Kufra in southern Libya into Darfur and Nyala. This supply network purportedly includes elements of Brigade 128 under Hassan al-Zadama and smuggling rings overseen by Haftar’s sons, Saddam and Belqasim.

The Triangle holds dual security and economic significance for Sudan’s Northern State. Strategically, it represents a potential breach point through which armed groups might infiltrate. Economically, if officially secured and regulated, it could serve as a formal trade corridor linking Sudan with Libya and Egypt. Its suspected mineral wealth, particularly in gold and uranium, could spark much-needed development, although ongoing instability threatens any such prospects.

Historically, the area has always been a smuggling hotspot, and illicit traffic has surged alongside worsening instability. Routes here facilitate the movement of weapons, narcotics, gold, and humans, managed by networks stretching from Darfur to Libya’s coast, exploiting the inhospitable terrain, lax oversight, and collusion by local actors.

A stateless governance project

This Libyan dimension to Hemedti’s backing must be seen within a broader geopolitical contest, as regional and international actors vie for influence across Sudan and the wider Sahel. Investigations by The Wall Street Journal and CNN have traced arms shipments from Haftar-controlled bases to the RSF, with logistical support from Russia’s Wagner Group. The US security outlet The Soufan Group has documented an economic alliance between Haftar and Hemedti built on fuel, gold, and arms trafficking routes traversing Chad, Niger, and Libya.

Beyond military expedience, the Haftar-Hemedti nexus rests on a shared ideology that scorns centralised state authority in favour of personal loyalty networks and informal economies. Both men emerged on the fringes of formal politics and pursued power through unconventional means: smuggling, mercenary forces, resource exploitation, and strategic regional ties. Their partnership also signals the rising role of local militias in a neo-colonial, post-colonial economy, a phenomenon scholar Edward Thomas terms “neoliberal militias”.

Meanwhile, Egypt remains a steadfast ally of Sudan’s regular army, whereas the UAE backs Haftar and supports Hemedti to safeguard its Red Sea and East Africa interests. Russia, via Wagner, invests heavily in Sudanese gold and is pursuing a military foothold in Port Sudan.

With entrenched external backers, competing regional agendas, and no clear political horizon for Sudan, conflict in the Border Triangle shows little sign of abating. Once a marginal desert patch, it has evolved into an open conflict zone where new alliances are forged and the region’s political geography is redrawn.

The Triangle is no longer a geographic afterthought. It has become a potent symbol of the struggle for power, wealth, and influence, stretching from Darfur to Benghazi and from Abu Dhabi to Moscow. Here, the humanitarian tragedy remains a perpetual sideshow as war-scarred refugees flee towards an uncertain future shaped more by militia maps than by official borders.

Quoted from Atar