How Thousands of Years of History Vanished in Sudan’s War

Sudan Events – Agencies

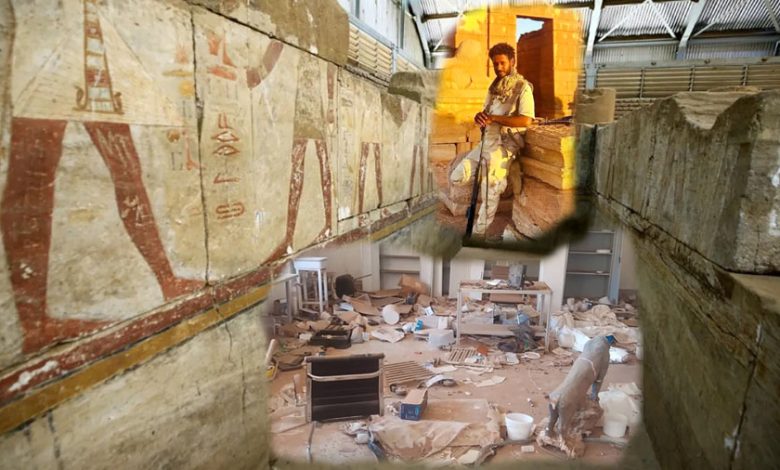

Since the looting of the National Museum in the early days of Sudan’s war between the army and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in April 2023, thousands of priceless artifacts have disappeared—many dating back to the Kushite Kingdom some 3,000 years ago.

Officials believe some pieces were smuggled across borders into Egypt, Chad, and South Sudan, but the vast majority remain untraceable.

“All that is left are the large, heavy items that could not be carried away,” said Rawda Idris, public prosecutor and member of the Sudanese committee for the protection of museums and archaeological sites.

At its height, the museum housed more than half a million artifacts spanning 7,000 years of African history. According to former antiquities director Hatem al-Nour, they “embodied the deep history of Sudanese identity.”

Today, massive statues of Kushite war gods stand guard over abandoned grounds beneath a roof blackened by shellfire. The rest of the collection has vanished.

“A War Crime”

Central Khartoum—where the museum stood alongside key state institutions—became a battleground when the RSF swept into the capital in April 2023.

Sudanese heritage officials were only able to return in March, after the army retook the city, to find their treasured institution in ruins.

The greatest blow, they say, was the loss of the famed “Gold Room,” which housed solid gold royal jewelry, small statues, and ceremonial objects.

“Everything in that room was stolen,” said Ikhlas Abdel Latif, director of museums at the Sudanese Antiquities Authority.

She explained that the artifacts were loaded onto large trucks, driven through Omdurman west of Khartoum, and transported to RSF strongholds in Darfur—before some later surfaced across the South Sudanese border.

Most of the stolen items belonged to the Kushite Kingdom, a Nubian civilization that rivaled ancient Egypt in wealth, power, and influence. Its legacy—once preserved in intricately carved stone and bronze relics adorned with precious gems—has now become another casualty of Sudan’s war between rival generals.

The conflict between army chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and his former deputy, RSF commander Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, has killed tens of thousands and created the world’s largest displacement and hunger crisis.

Pro-army officials accuse RSF fighters of looting the National Museum and other heritage sites, describing the destruction of artifacts as a “war crime”—an accusation the paramilitary group denies.

The Black Market

In September last year, UNESCO issued a global alert urging museums, collectors, and auction houses to “refrain from acquiring, importing, or transferring ownership of Sudanese cultural property.”

A Sudanese antiquities official told AFP that Khartoum is coordinating with neighboring states to trace the missing treasures. Interpol also confirmed to AFP its involvement in locating the looted pieces but declined to provide further details.

In the spring of 2024, “a group of foreigners” was arrested in River Nile State north of Khartoum carrying antiquities, according to prosecutor Idris.

Two antiquities officials also reported that another group contacted the Sudanese government from Egypt, offering to return looted artifacts in exchange for money. It remains unclear how the authorities responded.

Abdel Latif noted that Kushite funerary statues are in particular demand on the black market because they are “beautiful, small, and easy to transport.” But so far, specialists have not been able to track them—or locate any of the Gold Room’s treasures.

According to her, the sales take place within tightly knit smuggling networks behind closed doors.

$110 Million in Losses

The National Museum in Khartoum is far from the only cultural victim of Sudan’s war.

Former antiquities director Nour told AFP that the scale of its losses “should not overshadow the destruction of all the other museums, which are no less significant” in safeguarding Sudan’s heritage.

More than 20 museums across the country have been looted or destroyed, officials estimate, with total damages reaching around $110 million so far.

In Omdurman, the Khalifa House Museum stands scarred, its walls riddled with bullet holes and gouged by artillery fire. Once the seat of Sudanese authority in the 18th century, it now contains shattered glass and broken relics.

In Darfur, reports say the Ali Dinar Museum in the besieged city of El-Fasher—the largest in the region—was destroyed in fighting.

In Nyala, the capital of South Darfur, a local source said access to the city museum has become impossible.

“The entire area is now devastated. Only RSF fighters can move there,” the source added.

Abdel Latif confirmed that the Nyala museum, which had been recently restored after years of closure, “is now being used as a military base.”