Two Years into Sudan’s War: Tracing Looted Antiquities Remains Elusive

Sudan Events – Agencies

Majestic and solitary, the colossal statue of King Taharqa—who ruled the ancient Kingdom of Kush for more than two decades—now stands alone in the courtyard of Sudan’s National Museum in Khartoum. No longer surrounded by admirers or scholars, it is instead flanked by shattered display cases and broken statues, silently telling the story of a nation in ruin. Two years after the official announcement of the museum’s looting, the search continues for tens of thousands of artifacts that vanished into the fog of war, some of which have since surfaced sporadically in neighboring countries such as Egypt, Chad, and South Sudan.

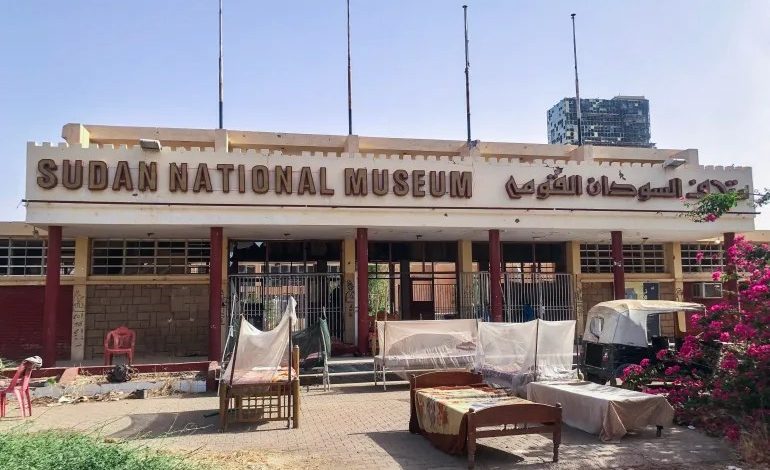

Rowda Idris, a prosecutor representing the Sudanese Attorney General’s office on the Committee for the Protection of Museums and Archaeological Sites, summed up the catastrophe bluntly: “Only the large or heavy objects that couldn’t be carried away survived.” At the museum entrance, what was once a lush garden of rare trees and a miniature Nile has become a barren patch of dry grass, guarded by silent statues of Kushite war deities beneath a roof scarred by shelling. Hatem al-Nour, former director of the Antiquities and Museums Authority, told AFP that the National Museum “housed more than 500,000 pieces spanning vast periods of history that together embodied Sudan’s deep cultural identity.”

In March this year, antiquities officials stepped onto museum grounds for the first time since the army recaptured central Khartoum. What they found exceeded their worst fears: devastation and the loss of priceless collections. The most shocking blow was to the “Gold Room,” which, according to Ikhlas Abdel Latif, director of museums at Sudan’s Antiquities Authority, contained “items beyond value—pure 24-carat gold pieces, some dating back nearly 8,000 years.”

Abdel Latif, who also heads the unit tracking stolen antiquities, confirmed that the Gold Room was “stripped bare.” Among the missing treasures were royal Kushite jewelry, gilded tools, and statues inlaid with precious metal. These relics belonged to a civilization that flourished alongside the Roman Empire, with capitals at Napata and Meroe in northern Sudan—an ancient culture as rich as Pharaonic Egypt, though far less recognized globally.

A War Crime Against History

The war between Sudan’s army, led by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), commanded by his former deputy Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, erupted in April 2023. It has since split the country, killing tens of thousands and displacing millions. Amid this catastrophe, the Sudanese government accused the RSF of “destroying artifacts and treasures chronicling 7,000 years of civilization,” calling it a war crime—allegations the RSF flatly denies.

Abdel Latif confirmed in June 2023 that the RSF had seized control of the National Museum, and earlier this year she revealed that looted artifacts were trucked from Omdurman to western Sudan before being moved toward the South Sudanese border.

The systematic plunder prompted UNESCO late last year to issue a global appeal urging the public to avoid trading in Sudanese antiquities, stressing the significance of the museum’s “important artifacts and statues of immense historical and material value.”

Racing to Recover a Stolen Heritage

Sudanese authorities have since launched a race against time. An official source at the Antiquities Authority told AFP that close cooperation with neighboring states is underway to trace and retrieve smuggled relics. Abdel Latif noted that Kushite funerary statues, in particular, are highly sought after on the black market: “They are beautiful, small, and easy to transport.”

The fate of the most valuable items, however, remains unknown. Neither the Gold Room collection nor the funerary statues have appeared in public auctions or on the parallel market. Abdel Latif believes much of the trade is happening discreetly within tight circles, adding that the government, in coordination with Interpol and UNESCO, is “monitoring all markets.”

Interpol confirmed to AFP that it is involved in efforts to track Sudan’s stolen antiquities, though it declined to disclose operational details. Some results have already emerged: Idris reported the arrest of a group in Nile River State, including foreign nationals, found in possession of artifacts. “Investigations are ongoing to determine which museum they came from,” she said. Sources within the Antiquities Authority also recounted an unusual case: a group that crossed into Egypt contacted Khartoum, offering to return stolen relics in exchange for money.

Destruction Across the Map

The tragedy of the National Museum is not isolated. Cultural heritage sites across Sudan’s war zones have suffered devastating losses. “More than 20 museums have been looted in Sudan—in Khartoum, Gezira, and Darfur,” Idris lamented. “We still don’t know the extent of damage in areas not yet retaken.” The National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums estimates recorded losses so far at around $110 million.

In Omdurman, the Khalifa House Museum still bears bullet holes and shell damage, with its 18th-century collections shattered. Al-Nour confirmed that the Ali Dinar Museum in El Fasher—the largest in Darfur—was also destroyed, along with museums in El Geneina and Nyala.

The Nyala Museum in South Darfur, according to a local source, became the center of “fierce fighting” and now lies in ruins. “No one can move there except RSF fighters,” the source said. Abdel Latif added that the site has been turned into “a military barracks”—a chilling symbol of Sudan’s cultural heritage crushed under the boots of war, as the memory of a nation is ground into dust.