Why Do Sudan’s Revolutions Fail?

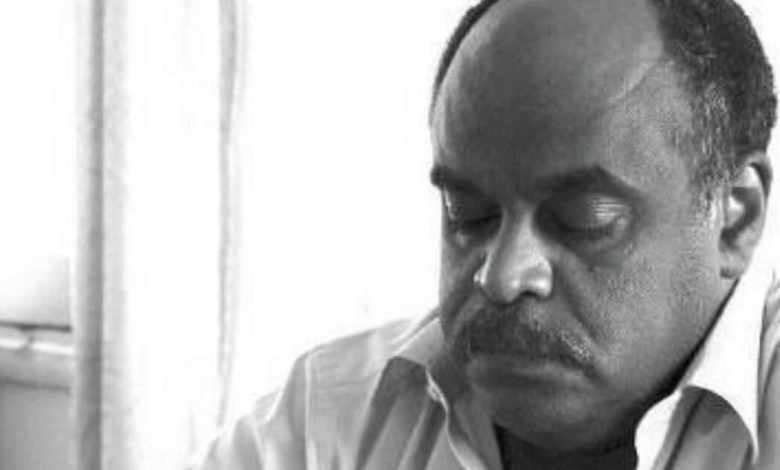

Dr. Al-Shafie Khidir Saeed

Despite the brutality of the war and the uncertainty clouding the future, and despite their total immersion in providing humanitarian assistance to civilians—saving lives and easing the burdens of hunger and disease—emergency response groups and resistance committees have not ceased to ask questions about the future and about Sudan after the war. They continue to revisit the past and to search the roots of hope, asking how the December Revolution can be reclaimed and its march toward victory completed.

To that end, they organized a dialogue inside Sudan on the anniversary of independence around a troubling question: Why do Sudan’s revolutions fail? I had the honor of contributing to this discussion, and I publish here the text of my response.

The failure of Sudanese uprisings and revolutions—October 1964, April 1985, and December 2018—to achieve their objectives is the cumulative result of several factors:

First: Deep structural causes that form a fertile ground for failure, including:

- The resilience of the deep state and its resistance to transformation. All Sudanese revolutions have confronted a “parallel state”—a network of interests embedded in the security, military, economic, and administrative institutions that emerged and solidified under authoritarian rule (Abboud, Nimeiri, Bashir). This network possesses institutional power that controls key levers of the state—the army, intelligence services, and a shadow economy—and uses them to mobilize tribal and military loyalties. Any genuine democratic transition implies dismantling this influence and holding it accountable; consequently, these institutional forces morph into an active counterrevolution, lying in wait for the moment to strike, as occurred with the coup of October 25, 2021. The network also has the capacity to infiltrate the revolutionary camp itself, fomenting internal disputes and unrest.

- Sudan’s revolutions as “center-based” revolutions. Concentrated in the capital and major cities, they prioritize political freedoms but fail to present an inclusive national project that decisively addresses the core issues fueling civil wars: the system of governance; equitable participation in power and the distribution of resources; confronting extreme centralization against the demands of marginalized regions; questions of identity and the relationship between religion and the state; and more. This leaves pockets of resentment and discontent that can be exploited to undermine nascent democracy.

- Regional and international dynamics. External actors often treat Sudan as an arena for influence struggles, supporting authoritarian regimes to secure artificial stability that serves their security or economic interests. They fear the success of a democratic “model” in Sudan that could threaten neighboring authoritarian systems, seek to exploit revolutions for external agendas, or withdraw support at critical moments—as happened with the December Revolution.

Second: Internal causes stemming from the mistakes of the revolutionary forces themselves:

- The absence of a consensual national project. Slogans may unite—“Freedom, Peace, and Justice”—but translating them into a detailed program of action remains elusive. Once the regime falls, sharp disagreements emerge over priorities and the nature of the transitional period, turning the revolutionary alliance into an arena of competition for power and influence rather than a workshop for nation-building.

- Weak institutional and leadership structures. Revolutions tend to rely on spontaneous popular mobilization and ad hoc leaderships that cannot prevent the hijacking of revolutions by traditional elites—elites that were part of the historical problem and lack a new vision or the courage to break decisively with the past.

- A lack of political acumen in managing the transition. Such acumen is essential to balance urgent popular demands with long-term structural reforms, and to manage relations with the military institution. Entering into an unequal partnership grants the military excessive political influence, while attempting to exclude it forcefully without adequate tools pushes it toward a coup.

Third: History teaches that revolutions rarely triumph on the first attempt

They typically follow winding paths of advances and setbacks before reaching their goals. The French Revolution (1789–1799) began by overthrowing absolute monarchy, passed through periods of terror and turmoil, witnessed a brief restoration of monarchy, and took decades before the principles of liberty, fraternity, and equality became entrenched. The English Revolution (1642–1688) began with civil war and the execution of King Charles I, followed by the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, before the Glorious Revolution of 1688 established a constitutional monarchy through a cumulative process. The German Revolution (1848–1849) spread across the German states but was militarily suppressed and failed at the time to achieve unification; yet it planted seeds that later bore fruit in 1871 under Bismarck. Sudan’s revolutions, since 1924, are no exception to this historical rule: each achieved gains and then suffered setbacks, but collectively they accumulated experience and formed a rising emancipatory trajectory, despite failed transitions and counter-coups.

Young people are the heart and fuel of the revolution. For it, they cheapen their own lives in pursuit of their greatest dream—carried with the highest degree of purity and ambition—of a modern, just state. Consequently, when revolutions falter, they pay the heaviest price. They feel they are waging an existential battle against a rotten system that has cut off their future, a future stolen twice: once by authoritarianism, and again by the failure to create a viable alternative. Their disappointment deepens when they watch their revolution devolve into conflicts among old elites speaking the language of the past, political deals and bargaining over positions while the country collapses—only for the scene to culminate in a devastating war (2023) worse than what they revolted against. Disappointment then turns into a profound psychological wound and a sense of double betrayal: betrayal by the old regime and betrayal by the political elites they assumed would lead change. Yet the sole remaining hope lies in learning these bitter lessons and building a new political movement from the rubble—more mature, better organized, and more determined to carry the revolution forward until the fundamental structural issues are resolved at their roots.

In the end, no matter how long it takes, and just as the revolutions of other nations eventually prevailed after long journeys, the victory of the Sudanese revolution is not merely a possibility—it is a historical inevitability. This is the objective course of history, which cannot be reversed. Revolutions are profound processes of social transformation that require time; each revolution builds on the experiences of those before it, and every setback creates more mature and effective conditions for struggle, alongside a rising awareness—especially among the youth, the soldiers of the revolution, who constitute the majority of the population.