Sudan and the Second “Lifeline” Operation

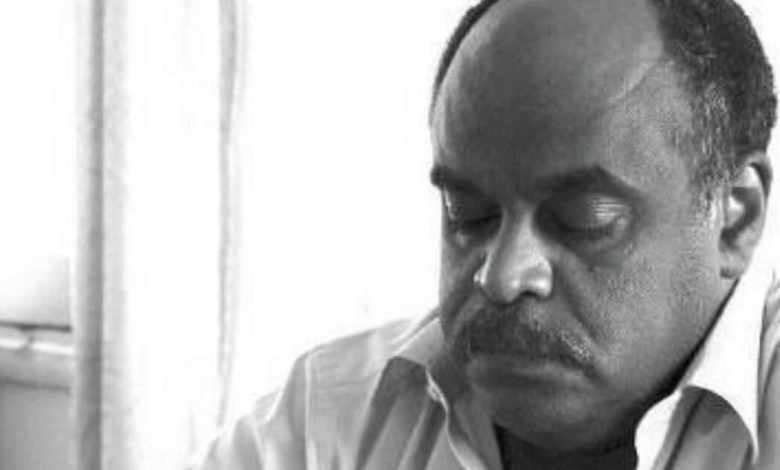

Dr. Al-Shafi’i Khidr Saeed

Death by artillery shells and bombs, death by starvation and lack of food and drinking water, death due to the spread of diseases and the absence of medicine and environmental health, and death from the destructive rage of nature… All are among the enemies of life that have dug their claws into the body of the nation and its people, turning Sudan into a symbol of extinction and a vessel of devastation. All of these tragedies are human-made, but not by just any human; they are caused by those responsible for a war that has dragged on and spread, both in breadth and depth, unleashing one of the greatest humanitarian catastrophes of our time. Therefore, the urgent priority today, which must concentrate all efforts, is to address this humanitarian disaster.

However, the main question remains: Can we address this catastrophic situation before reaching a ceasefire? Can humanitarian aid flow without being looted, and can aid workers operate without being targeted by snipers and fighters? Dr. Salah Al-Amin, a Sudanese UN expert who has long represented United Nations agencies in disaster prevention in several conflict zones around the world, answers this question affirmatively. He shared his insights with us in a message that we felt compelled to share with our readers in this article.

Dr. Salah says: More than 35 years ago, the United Nations and its partners, in coordination with the Bashir government and the leadership of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) led by Garang, planned, organized, and managed what became known as the “Lifeline Operation.” This operation successfully delivered humanitarian aid, including food, water, health, education, and protection, to millions in southern Sudan. It reached very remote areas via dirt airstrips built by the operation, after many had thought that the war and its people had become a forgotten cause.

The Lifeline concept began with a simple service provided by the Economic Security Team of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), responsible for providing economic assistance. The team, led by a veterinarian, was working in a border area between Sudan and Kenya, where they offered a livestock vaccination service that was warmly welcomed by the local population. The operation then evolved and continued for 15 years, becoming the largest and most distinguished humanitarian coordination effort in the history of global humanitarian responses to date. The administrative and logistical operations of the Lifeline were managed from Lokichogio in northern Kenya, near the Sudanese border. An agreement was signed between the Khartoum government and the SPLA, allowing flights on specific days of the week from Lokichogio airport into southern Sudan. The Sudanese side was represented by the government’s Humanitarian Aid Commission, while the SPLA was represented by its Sudan Relief and Rehabilitation Agency (SRRA), its humanitarian affairs organization.

Regarding the delivery of humanitarian aid to civilians today, as the international community deals with two warring factions—the army and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF)—Dr. Salah wonders: Will we witness a second “Lifeline Operation” in Sudan? Will the Adré area become another Lokichogio? He also answers this affirmatively, stating that the recent Geneva meetings resulted in understandings between the warring parties that allow the passage of humanitarian convoys to war zones. Leaks from closed-door negotiations in Geneva confirm that American aid, the World Food Programme, and the World Health Organization have been allowed to send convoys across the Adré border crossing between Sudan and Chad. This could serve as a pilot project, and its success might encourage the international humanitarian community to plan another Lifeline operation. Leaked information includes a map suggesting potential crossings proposed by both the Port Sudan government and the United Nations. These are not all border crossings between Sudan and its neighbors; some are internal crossings proposed between areas controlled by the Sudanese army and areas under the control of the RSF. Dr. Salah expects the plan to include other crossings and airports from neighboring cities in South Sudan, and that the Port Sudan government will insist on its constitutional right, as a de facto government, to issue a “no-objection” certificate that allows aid and its personnel to enter or even move within Sudanese territories. He points out that this has already begun when the Sovereignty Council in Port Sudan, by its decision, monopolized the authority to issue these permits, which were previously issued by the Humanitarian Aid Commission.

On the other hand, Dr. Salah mentions that the RSF has shown readiness to protect the movement of aid convoys and their workers in its areas of control. To the extent that their delegation participating in the Geneva negotiations met with senior officials at the ICRC and requested that the ICRC activate its mandate under the International Humanitarian Law (IHL) to train RSF fighters in the knowledge and adherence to IHL and the protection of aid convoys. It is well known that such training is a core task of the ICRC, provided to combatants in all war zones. However, Dr. Salah alerts us to a very important point: the most crucial and greatest element of the Lifeline Operation, yet currently absent, is the local communities on the ground, who are the ultimate beneficiaries of the humanitarian aid distribution. Therefore, it is extremely important that international humanitarian organizations insist on coordinating with local communities in the process of distributing and delivering aid to beneficiaries. Partnerships can be formed with civil society organizations in cities, villages, and neighborhoods to ensure that aid reaches those who need it. In addition to training, workshops, and expertise gained from other conflict zones outside Sudan, international organizations will benefit from the accumulated experiences of Sudanese local communities in sharing food and medicine, as well as in managing the war economy and coping mechanisms that have kept Sudanese people alive thus far.

So, does Dr. Salah’s talk inspire hope in this dark horizon?