Reports

Biden needs to pressure the UAE to help end Sudan’s civil war

By the Editorial Board

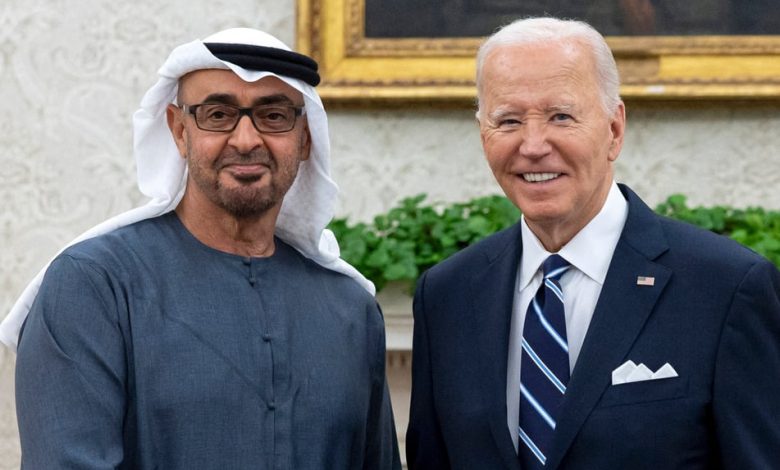

United Arab Emirates President Mohamed bin Zayed al-Nahyan visited the White House Monday, a first for an Emirati leader. The high-level attention underscored deepening U.S. ties with a key Gulf Arab ally amid the ongoing wars in Gaza and across the Israeli-Lebanese border. The Biden administration announced a range of new areas for cooperation with the UAE, including artificial intelligence, space exploration, clean-energy technology and defense. President Joe Biden designated the UAE a “major defense partner.” India is the only other nation to have received that label, which allows for closer military cooperation, including joint training and exercises.

On a different subject, though — Sudan’s civil war, and the UAE’s role in fueling it — the meeting produced a more mixed message. A joint communique saved fewer than 250 of its nearly 4,000 words for the topic. That’s not many for a conflict that has seen up to 20,000 people, mostly civilians, killed and parts of the capital, Khartoum, reduced to rubble. Some 10 million people have fled their homes, another 26 million people face a risk of hunger, and there are warnings of famine or potential genocide in the Darfur region.

Sign up for Shifts, an illustrated newsletter series about the future of work

To be sure, the United States and the UAE expressed “deep concern” and “alarm” at the situation, coupled with their “firm and unwavering position” in favor of an immediate end to the fighting. “Both leaders reaffirmed their shared commitment to de-escalate the conflict,” the statement said. Conspicuously absent, however, was specific mention of the UAE’s own role in providing weapons, funding and intelligence to one side: the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), whose troops have been accused of ethnic cleansing against the Black, non-Arab Masalit people of Darfur.

Story continues below advertisement

The UAE is the main backer of the RSF, which is commanded by Gen. Mohamed Hamdan “Hemedti” Dagalo. Using a staging area in neighboring Chad, the Emiratis have funneled advanced weaponry to the RSF and used Chinese-made Wing Loong II drones, with a 1,000-mile range and a 32-hour flight time, to deliver battlefield intelligence. The UAE has denied this, saying its presence in Chad is to assist Sudanese refugees and treat the wounded in a field hospital. But independent investigations, including by the New York Times, have found that the UAE’s humanitarian mission acts in part as a cover for military support of Mr. Dagalo’s forces.

Follow Editorial Board

Follow

Mr. Dagalo’s RSF — an offshoot of the Janjaweed Arab militia — is responsible for the ongoing atrocities in Darfur, which bear a sickening resemblance to the violence of the early 2000s. As was the case in Darfur at that time, there have been substantiated reports of summary executions of men and boys, and Masalit women being subjected to horrific gender-based violence, including sexual slavery and rape.

The UAE is far from the only outside power intervening in the 18-month-old war, which pits Mr. Dagalo’s RSF against what’s left of the Sudanese Armed Forces, or SAF, commanded by Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan. Indeed, as has unfortunately been the case for many of Africa’s internal wars throughout history, this one has morphed into a proxy fight among geopolitical rivals. The UAE’s long-standing Middle East rival, Iran, backs Mr. al-Burhan; it has supplied drones to the SAF that helped it retake territory from the RSF. Russia formerly backed the RSF but now supports Mr. al-Burhan. Moscow and Tehran both covet future access to Sudan’s strategically important ports along its 530-mile Red Sea coastline — as does the UAE.

Story continues below advertisement

The United States, too, seems to see Sudan through the prism of geopolitics. Aligning with the UAE as a moderate Arab state might make sense in a broader strategic context; that country can serve as a regional counterweight to Iran, and the UAE is being eyed for a future role in rebuilding war-torn Gaza. The UAE’s role in Sudan makes it Russia’s enemy, too. Hence the implicit tension between Mr. Biden’s warm words for the UAE’s president in Washington and the valedictory speech he delivered to the United Nations the next day. “The world needs to stop arming the generals,” the president said, “to speak with one voice and tell them: Stop tearing your country apart.”

For now, at least, this is the administration’s position: to decry the human cost of Sudan’s war in general terms, while pursuing closer ties to the UAE, without demanding a clear public commitment that the UAE stop supporting a faction responsible for some of the conflict’s worst atrocities. If that sounds difficult to reconcile with the United States’ highest principles, it’s because it is.