Opinion

The Umma Party and the Resounding Collapse in the Path of Submissive Settlement (2 – 2)

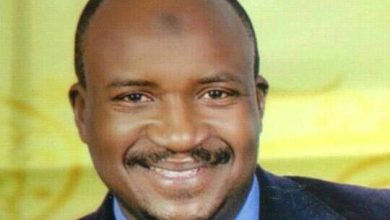

Hatem Hassan Bakhit

**8//**

Mr. Mubarak Al-Fadil, from the lineage of Al-Mahdi, whose symbols have historically been associated with the claim to the leadership of the Umma Party both politically and sectarily when possible, is a figure who has remained controversial in his various stances, whether when participating in governance or opposing successive political regimes. This may be due to his educational background, having completed both secondary and university education in Beirut, which undoubtedly played a role in shaping the initial foundations of his political thinking, which leans somewhat towards independence in adopting political visions and choosing available options over collective thinking. This is a reflection of the nature of the student political and organizational activity climate in Beirut, as astutely described by the Palestinian revolutionary leader Dr. George Habash when a group of enthusiastic Palestinian revolutionary youth in Beirut’s institutes and universities split from the Democratic Front, led by Nayef Hawatmeh, and joined the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. Habash said at the time, “The motives behind this collective schism are not only due to a lack of belief in our struggle but also reflect a clear desire for a strong sense of independent identity within the organization, demanding the freedom to adopt their detailed options within the broader framework of the organization.” This captures the dynamic of student political life in Beirut, which requires careful attention to avoid future splits.

Despite Mr. Mubarak Al-Fadil’s dynamic personality and his constant controversy, he has not enjoyed consensus within any group he chose to ally with or engage in joint political work. His inclination towards independent stances away from collective positions of these alliances or coalitions is evident. For example, during the armed National Front against the May regime, the parties comprising this front were not fully satisfied with him, despite his strong friendships with the Federalists, Islamists, and other coalition groups such as the Islamic Socialist Party or Revolutionary Committees. Similarly, dissatisfaction persisted even with the forces his party sought to ally with to form coalition governments, whether the Federalists, Islamists, or Southern parties during the third partisan period. Furthermore, he did not achieve full satisfaction when he led the Democratic National Gathering against the Salvation regime until he made the radical independent decision to break away from his party, the National Umma Party, and its historical leader Imam Sadiq Al-Mahdi, by declaring the birth of the Reform and Renewal Umma Party in 2000 as a standalone party. However, this new party under his leadership also quickly fractured due to his methodology, leading to groups splitting off under names derived from the Umma Party’s legitimacy, adding their own flavor for distinction, but purely for distinction’s sake.

Mr. Mubarak Al-Fadil’s involvement in the governance of the Salvation regime was constantly surrounded by mutual doubts and discomfort, even after he became an advisor to the president. When the prime minister selected him along with two others to be his deputies, the presidency did not recognize him or the others as deputy prime ministers. The Minister of Presidential Affairs remained the primary figure following the prime minister in the government, with no recognition of deputy prime ministers in the memory of the presidency.

**9//**

Through Mr. Mubarak Al-Fadil’s governmental positions and his leadership roles in opposition coalitions against various regimes, as well as his wide network of internal, regional, and international relations, he has gained extensive experience. Many saw him as a potential key player in establishing stability after the change in April 2019, despite some protesters’ harsh treatment of him in the sit-in square, where they harassed him, rejecting his presence among them. Mr. Mubarak sincerely and diligently sought, after the change, to offer advice and counsel to the state’s leadership, particularly in complex matters across various fields, especially the economic ones.

When the war broke out, his declared position was clear: it was not in the country’s interest, and he did not equate the army with the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). He began advocating that the solution to stop the war lay in implementing the Jeddah agreement, which called for the RSF militias to leave residential areas and civilian establishments. In doing so, his stance became distinctly clear, differing greatly from that of the National Umma Party and its leadership, which remains ambiguous in its support of the RSF’s stance, with some even justifying the militia’s occupation of citizens’ homes. This has been Mr. Mubarak Al-Fadil’s position throughout eleven months of war, until the appointment of the American envoy Tom Perriello, who proposed a settlement plan that Mr. Mubarak Al-Fadil eagerly embraced. This has led him to adopt completely different positions, raising many questions about how his stance on the war and how to stop it has drastically changed. Among these positions:

– He called on the army leadership to participate in the Geneva conference, which was called for by the American envoy, without insisting on representing the government, as demanded by the state leadership. Mr. Mubarak ignored that the American envoy deliberately bypassed the government and its concerns, indicating a lack of recognition of the government and reinforcing the American notion that the war is between two leaders, not between the state and a military force that rebelled against it. This serves Tom Perriello’s agenda and that of the RSF, marking a regression from his earlier stance.

– He urged the army leader to comply with the envoy’s request to visit Port Sudan and meet with Al-Burhan only in his plane on the runway, trying to justify this arrogance and disregard for the country’s sovereignty.

– Mr. Mubarak Al-Fadil made an urgent and strange appeal on the X platform, warning of an imminent genocide in the besieged city of El-Fasher, which is surrounded by militias bombarding civilian neighborhoods, markets, and displacement camps. It was as if he was certain that its fall was only a matter of time, failing to condemn the attacking militia or acknowledge the resilience of the army and the armed movements defending the city ferociously, inflicting heavy losses on the militia after over 520 attacks without the militia advancing. Meanwhile, Mr. Mubarak Al-Fadil appealed to the U.S., the U.N. Security Council, and major countries to urgently intervene to save El-Fasher from a fate similar to that of Al-Geneina. Hence, it is not surprising that some of these countries made the bizarre call for the army and armed movements to withdraw from El-Fasher, despite their defense of the city and its residents, rather than demanding that the militia and its supporters stop their barbaric attacks on civilians.

**10//**

When Mr. Mubarak Al-Fadil challenged Imam Sadiq Al-Mahdi for leadership of the National Umma Party, one of his public justifications was the need for leadership renewal, assuming that Sadiq Al-Mahdi had reached an age of senility and should loosen his grip on the party’s affairs, opening the door for real participation by the party’s leadership in handling key responsibilities (as if political work had a retirement age). Although some agreed with this at the time, Mr. Mubarak Al-Fadil now faces the same challenge. At over 75 years old, and with the war’s end not imminent, extending perhaps through reconstruction and beyond, this could see Mr. Mubarak Al-Fadil reach 80. The question arises: will he relinquish leadership of the Reform and Renewal Party to younger, more nationally spirited leadership, or will he pass on a party that has embraced the proposals of Tom Perriello, the American envoy, who is ignorant of Sudan’s conflict and oblivious to the war’s causes and continuations? This marks a shift from the party’s clear, principled stance during the eleven months of war to his sudden enthusiasm for the Geneva talks, advocating participation without grasping their ultimate goals or outcomes.

In sum, the article critically examines the internal divisions and leadership struggles within the Umma Party and Mubarak Al-Fadil’s controversial role throughout Sudan’s turbulent political landscape, especially during the ongoing war. The question remains whether he will continue to lead his party in a way that aligns with external interests or step down for younger, more patriotic leadership.