Is Sudan Witnessing a Proxy War Between Egypt and the UAE?

Ahmed Metarik – Cairo

In light of the deteriorating relationship between Cairo and the Sudanese Rapid Support Forces (RSF): “If you export even a cup of gum arabic, a Sudanese bean, or an animal to Egypt, you will face severe penalties.” With these words, King Abu Shotal, a leader of the RSF, warned traders in areas under his control against exporting any products to Egypt in a televised speech.

This decision marked a new escalation in the recently deteriorated relationship between Cairo and the RSF. The RSF’s leader, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemedti, accused Egypt of directly intervening in the war by supplying the Sudanese army with “weapons and drones.” He even claimed that Egyptian warplanes had bombed several of his camps.

Egypt, for its part, has categorically denied these accusations, asserting that its role in resolving the crisis is limited to “stopping the war, protecting civilians, and enhancing international response to relief efforts.”

How does Egypt view the Sudanese crisis? Is it in its interest to side with one faction over the other? Will its intervention bring an end to the war, or will it lead to further escalation?

Egypt Only Supports Official Institutions

Ayat Abdelaziz, an expert in African affairs, stated that until recently, Egypt had tried to remain neutral toward all parties. A simple example is that when the RSF detained an Egyptian battalion, Cairo did not respond harshly but instead used calm mechanisms to peacefully retrieve its soldiers. Subsequently, Cairo hosted a conference bringing together various Sudanese forces to bridge their differences.

She continued in her interview with Al-Hurra: “Over time, the RSF took a different path, complicating its relationship with Egypt after Hemedti aligned with Ethiopia and received significant support from it.”

Dr. Iman El-Sharawy, an African affairs researcher, affirmed that Egypt’s foreign policy is based on several principles, including restricting its support to official institutions, as it does not back militias or rebel forces.

She added during her interview with Al-Hurra: “When we apply this to Sudan, we understand that Egypt supports the army as it is the most important official institution in Sudan.”

Ayat Abdelaziz deemed this choice logical, saying, “In Egypt’s quest to strengthen the Sudanese state, should it support a militia or the official Sudanese army? It is in Cairo’s interest for Sudan to be stable, which can only be achieved if the army is strong and controls the territory.”

Recently, the military institutions of both countries have drawn closer, reflecting their unified stance on the Nile Dam crisis and rejecting attempts to renegotiate Nile water quotas. On the other hand, the RSF has fostered a good relationship with Ethiopia, Egypt’s major rival in Africa.

Hany Suleiman, director of the Arab Center for Research and Studies, stated that Egypt is not an ideological state with a project it seeks to spread, nor is it a state pursuing narrow gains. Therefore, it has taken a “logical and non-greedy” stance on the Sudanese crisis, focusing on securing its national security lines in Sudan by supporting its national institutions.

John Ishiyama, a professor of political science specializing in African affairs, told Al-Hurra that it is not surprising if reports of Cairo’s military intervention in support of the Sudanese army are accurate, as Cairo has supported it for a long time. Thus, these airstrikes would merely be another episode in this support.

This support has manifested in various ways, including Cairo’s rejection of calls to deploy an African peacekeeping force as a means to end the conflict, announcing its “firm rejection” of it. El-Sharawy said, “Such a force would not calm the crisis as it would consolidate the current situation in which Hemedti’s forces control larger areas of land, giving him the opportunity to regroup, receive more weapons from abroad, and reorganize.”

She added, “How can a force be deployed amid ongoing fighting? It is supposed to be deployed only after the situation calms following a peace agreement. This scenario harms Sudan and Egypt’s national security and benefits the RSF.”

Egypt’s military cooperation with African countries, such as Somalia and Eritrea, is not unprecedented, so it wouldn’t be surprising if Sudan joined them given its growing importance to Egypt’s national security as a neighboring country that once shared a political union with Egypt for 43 years.

These maneuvers not only encircle Hemedti’s forces but also his largest ally, Ethiopia, which Egypt seeks to encircle with a coalition of African countries supportive of its policies. Abdelaziz suggested that there needs to be a broader perspective: Egypt faces threats not only from the Nile but also from its maritime security if Ethiopia extends its borders to the Red Sea, potentially affecting navigation in the Suez Canal. All these intertwined issues require unconventional plans for resolution.

Through these moves, Egypt tries to send messages to all regional powers that Cairo is no longer inclined to isolate itself as it once did in the past, and that it is capable of creating “new cards” to pressure Ethiopia during the stalled Nile Dam negotiations.

Why Does Egypt Oppose Hemedti?

“Hemedti’s victory would have a negative impact on Egypt’s national security because it could lead to further divisions within Sudan itself, with new regions—apart from the south—like Darfur, for instance, breaking away,” said El-Sharawy.

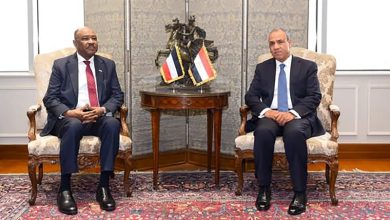

According to Ishiyama, Ethiopia does not view the Sudanese army as a friend, despite Burhan’s visit last month, especially as tensions persist over the disputed “Fashaqa” border region. Thus, Addis Ababa sees a weakened Sudanese army as beneficial not only due to its support for Egypt’s stance but also because of the border disputes between them.

Conversely, Ethiopia prefers dealing with Hemedti, who can disrupt Egypt’s calculations on many fronts, such as giving Addis Ababa an advantage in the Nile Dam crisis and hindering Egypt’s economic projects in Africa, like linking Lake Victoria to the Mediterranean Sea. Hemedti could also turn Sudan into a base for hosting armed groups seeking to carry out military operations inside Egypt and spread chaos, a dilemma Cairo faced with Libya after the fall of Muammar Gaddafi’s regime.

During the era of former President Omar al-Bashir, who had Islamist inclinations, many extremist terrorist groups, including Al-Qaeda and Egyptian Jihad, trained in Sudan. These groups clashed with Egyptian security forces in Upper Egypt.

Several assassination attempts on Egyptian ministers, such as former Interior Minister Hassan Al-Alfi and the late Information Minister Safwat El-Sherif, were planned from Sudan. The most notable attempt was the assassination of former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak in Addis Ababa, planned by Mustafa Hamza, the head of the Shura Council of the Egyptian Islamic Group, and Osman Mohamed Taha, deputy of Hassan al-Turabi, the founder of Sudan’s Islamic movement.

Cairo is not keen to repeat such scenarios by supporting a government loyal to it, ensuring the minimum protection of its interests and national security in the region.

Egypt and the UAE: Allies in Conflict

In recent months, Sudan has repeatedly accused the UAE of directly supporting the RSF, leading to verbal clashes between their representatives during a UN Security Council meeting on Sudan. There have been incidents like Sudan bombing the UAE ambassador’s residence in Khartoum and accusations that Abu Dhabi sent hundreds of aircraft loaded with weapons to Hemedti’s militias.

Hemedti established a strong relationship with the UAE since he served as the intermediary between the Sudanese army during the preparation for Operation Decisive Storm. Since then, their relationship has strengthened as “the UAE… is committed to achieving its goals by any means necessary, unlike Saudi Arabia and Egypt,” according to an anonymous political source.

According to Ayat Abdelaziz, the UAE has long sought to shed its image as a small, limited-impact state to play larger roles, particularly in Africa, where it seeks to expand its influence. She added that its relationship with Hemedti is complex, as he seeks any legitimacy for his forces to confront the Sudanese army, whose legitimacy cannot be questioned. Thus, he would be willing to accept any international support in exchange for any benefits requested.

Ishiyama said that the UAE believes that a weak Sudanese government is the best option to protect its economic interests in the region. Therefore, it sees its support for the RSF as a means to gain access to Sudanese lands, seaports, and agricultural resources—activities that the Sudanese army has opposed, while Hemedti’s forces would be more willing to turn a blind eye.

According to an anonymous source, “Besides the gold mines that Abu Dhabi imports heavily, Hemedti will grant the UAE a port on the Red Sea, achieving its strategic goal of controlling several African ports in this crucial region of the world.”

The source concluded in his interview with Al-Hurra that the UAE’s presence on Egypt’s border is not in Cairo’s interest given its current policies.

The UAE has repeatedly denied allegations that it sent military support to any of the warring parties in Sudan. In July, the UAE’s UN mission described such claims as “lies, misinformation, and propaganda spread by some Sudanese representatives.”

Nonetheless, UN sanctions monitors have described the claims that the UAE provided military support to the RSF as “credible.”

Earlier this month, Egypt assumed the presidency of the African Union’s Peace and Security Council. Recently, the council called for reopening the AU liaison office in Port Sudan, where the Sudanese government is currently based.

The UAE indirectly criticized this move, as its affiliated media reported that the council’s “current composition” had clearly sided with the army.

This indirect exchange of words reflects a significant disagreement between Egypt and the UAE, two allies in numerous issues such as supporting Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, the influential figure in eastern Libya.