Opinion

Eritrea: When Love Gets Mixed with Blood!! (1)

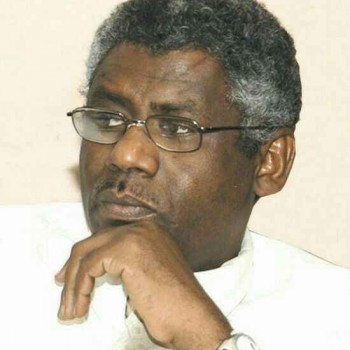

As I See

Adil El-Baz

1

Every time I hear or read news about Eritrea, a series of memories of my Eritrean friends – or rather, “Eritreab” (lovers of Eritrea) – come to mind, from Abu Al-Qasim Haj Hamed to Majed Youssef. These friends shaped my love and admiration for the Eritrean people and their immense struggle for freedom, which they fought for over thirty years (from the start of the revolution in 1961 to the announcement of victory in 1993).

Eritrea has a long and inspiring story of the struggle for independence, recounted by generations of Eritreans who paid for it with tears and blood. When we met President Isaias Afwerki, he seemed to understand, more than any other leader in the region, the significance and importance of resisting the “occupying invaders” who seize homelands. For this reason, he strongly aligned with Sudan’s stance and stressed the need to support it in its current struggle against invaders and mercenaries. He repeatedly emphasized in our meeting the importance of ending the war in Sudan in favor of the Sudanese army, as this is essential to keep Sudan united and to maintain the cohesion of what he called “the neighborhood,” which includes the Arabian Gulf, the Horn of Africa, and the Red Sea – a concept that I heard from President Isaias for the first time and that requires further detail, which we may return to later. Sudan was present throughout the Eritrean struggle from its inception in 1961, and since then, and even before, our love for Eritrea has been bound by blood.

2

When I asked President Isaias during our recent meeting in Asmara as part of the Sudanese media delegation about the strange stance of Sudan’s neighboring countries regarding the conflict in Sudan and their abandonment of the Sudanese people – and even their support for the rebels – he exploded in anger, saying: “Some of these countries are not real states and cannot be considered as such; others have no control over their decisions.” I was perplexed by the intensity of his anger but then recalled the tales of betrayal recounted by my teacher and friend, Mohammed Abu Al-Qasim Haj Hamed. He told me that the Eritrean revolution was let down by everyone in the region (except Sudan). In his notes on the Eritrean revolution, Haj Hamed wrote: “Africa considered the Eritrean revolution a ‘separatist movement’ to which the 1964 African Summit’s resolution on maintaining colonial borders applied. However, this decision actually favored Eritrea, as it was Ethiopia that abolished the colonial border with Eritrea and occupied it. Yet the Africans overlooked this situation when they agreed to make the Ethiopian capital the permanent headquarters of the Organization of African Unity in 1961 – the same year Ethiopia annexed Eritrea.”

On the Arab front, Egypt, led by Nasser’s vision, viewed the matter through the lens of its strategic reliance on Ethiopia, as 86 percent of its water came from Ethiopian sources, in addition to the relationship between the Ethiopian Coptic Church and the Alexandrian Patriarchate. This led Cairo to coordinate with Addis Ababa on African affairs. Despite repeated Eritrean appeals between 1961 and 1969, no substantial Arab support materialized except for limited donations and solidarity campaigns. The Eritrean revolution launched its military operations in 1961, and although the United Nations had issued a federal resolution in December 1950 to establish a contractual relationship between Eritrea and Ethiopia after Italy’s withdrawal from Eritrea in World War II, this international body remained silent when Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie lowered the Eritrean flag, dissolved the Eritrean parliament, and dismantled the federal government in 1958, formally annexing Eritrea into his empire by 1962.

3

Eritrea thus experienced betrayal by its close neighbors (except Sudan), with everyone pursuing their interests, regardless of the Eritrean people’s just cause. In a similar vein, Sudan is currently waging its struggle and facing similar abandonment from neighbors, allies, and friends (except Eritrea). This uncanny resemblance is striking – the same traits and shared destiny in a struggle with the Eritrean people.

President Isaias and his generation know the bitterness of betrayal. His anger stemmed from seeing the same betrayal repeat itself toward Sudan, which has given so much to its Arab brethren and African neighbors, contributing knowledge and expertise to help establish their countries. When Sudan faced an invasion of mercenaries and the ruthless Janjaweed, some conspired, funded, and facilitated weapons for the aggressors. What betrayal could be greater than this?

4

To be fair, Haj Hamed noted in his Eritrean revolution memoirs that (the positive stance of the Syrian separatists before the Baath Party’s takeover in 1963 was notable, as three prominent Arab figures sympathized with the Eritrean plight. They were: Haj Amin Al-Husseini, the Grand Mufti of Palestine; Moroccan prince Abdul Karim Al-Khattabi, leader of the Rif Revolution against Spain; and Syrian officer Abdel-Haq Shehada, a supporter of Adib Al-Shishakli’s coup in Syria). These three facilitated contact between the late martyr Osman Saleh Sabbe and the “separatist” leadership in Damascus, who received thirty young Eritreans for training at the Qatana camp, supplying them with 80 tons of arms and ammunition, thus laying the military foundations of the Eritrean revolution.

The truth that Haj Hamed did not mention is that he was the architect behind relations between the Syrian separatists and the Eritreans, opening an office for them in Lebanon. This earned him the lasting gratitude and recognition of the Eritreans to this day. When I told President Isaias that I was a student and friend of Haj Hamed, he did not believe it, but he shook my hand again and took a picture with me in hopes that it would turn out beautifully to revive those fond memories. Unfortunately, it didn’t turn out well because the photographer was Al-Taher Sati (may God not forgive him).

5

Finally, Haj Hamed recounts one of the amusing tales of how fighters and weapons reached Eritrea after the Baath Party came to power in February 1965 “through very special means,” orchestrated by Sudanese Prime Minister of the October 1964 Revolution, Sir El Khatim El Khalifa, along with presidential affairs minister Mohammed Gabara El-Awad, justice minister Rashid Al-Taher, and Sudan Airways director Yusuf Bakhit – all without the knowledge of the Sudanese army commander or the ministers of foreign affairs and interior. When the Syrian shipment was eventually discovered (after it had reached Eritrea), the prime minister denied knowing about it, while the late justice and presidential affairs ministers went into hiding in their villages.

6

Sudan’s support for the Eritrean liberation movement remained steadfast (with few exceptions by the October Revolution government) until Eritrea gained independence. But the bond of “love through blood” with our family and friends in Eritrea began even before the Eritrean revolution and runs deeper than that.

(To be continued.)