Prospects of the Proposed National Project

As I See

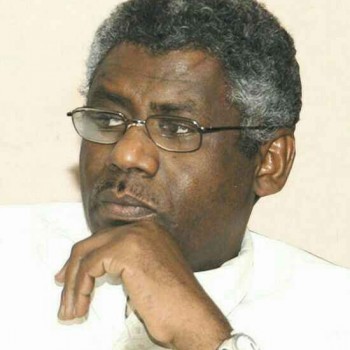

Adil Al-Baz

1

The document titled “Proposal for the National Project,” issued by the political forces meeting in Port Sudan, has not received sufficient attention in the political arena. It has not been widely discussed by political factions that did not participate in the Port Sudan dialogue. Moreover, opposition forces abroad have refrained from commenting on it, and no serious debate has taken place in media platforms. The document was released under the title “The Path to Peace and Stability,” emphasizing in its introduction the pursuit of unity and peace while aiming to achieve democratic transformation by the end of the transitional period.

2

In my view, this project deserves discussion for several reasons. First, the political forces that convened have consistently supported the armed forces from different positions without having a unifying framework for their ideas and programs. The key questions have been: What are the points of disagreement among these forces? Where do they agree? And what is their political project? No one has been able to answer these questions, as their statements have mostly been fragmented and vague, offering little clarity. Even the government or ruling authority has not fully understood the perspectives of these political forces or their specific demands, despite frequent meetings with officials. These forces are often accused of merely seeking a share of political power, despite the country’s difficult circumstances.

3

The second reason is that these forces have never come together on their own to develop a clear vision for the foundational or transitional period. They are often accused of merely acting as a political backing for the military without having an independent political vision, either individually or collectively. Perhaps the government’s invitation for them to meet in Port Sudan was intended to get to know them better, understand their vision and demands, and explore what they might propose for governing the country during the transitional period.

4

The third reason is that this national project, presented by the political forces, is not solely directed at the domestic audience but also sends a message to the international community. The global actors who previously believed there were no influential civilian forces must have realized, after this conference, that there exists a significant political, civil, and societal bloc in Sudan. This bloc is not composed of the weak and ineffective forces that international players have frequently engaged with in African capitals.

5

One of the most commendable aspects of the national project document is that it does not claim to be the ultimate solution for Sudanese politics. Rather, it has been presented as a vision or proposal put forth by those who gathered in Port Sudan for the government’s consideration. It remains merely a political proposal by Sudanese forces—something they are fully entitled to present—without invalidating the views of those who did not attend the Port Sudan meeting or were not invited.

6

The national project, in its entirety, reflects a spirit of consensus, focusing on what unites Sudanese people rather than what divides them. All the issues it presents are open for discussion, and the document repeatedly emphasizes ending any group’s monopoly on power. It rejects exclusion and affirms everyone’s right to political participation and nation-building—except for those who have been convicted of war crimes (note: convicted, not merely accused).

7

At the beginning of the document, the concept of “national principles” is introduced—these are principles agreed upon by patriotic Sudanese (not foreign agents). The principles start with national unity and end with sustainable peace. The document also proposes initial ideas regarding two periods: a foundational period of one year and a transitional period with no predefined time frame, leaving its duration to be determined by the planned Sudanese-Sudanese conference before the foundational period concludes.

In my opinion, a single year as a foundational period for a country devastated economically and socially is insufficient to lay any solid groundwork. The “Proposal for the National Project” outlines 16 goals to be achieved within this period, yet accomplishing even one of them might take months. Therefore, it would be more practical to extend the foundational period to at least two years, allowing time to address some of the massive destruction the country has suffered. Moreover, the war has not yet ended and may persist longer than expected due to the growing external conspiracies.

8

The national project proposes governance structures for the transitional period, recommending a federal system and related structures. However, it leaves the details to be determined by the Sudanese-Sudanese dialogue conference.

9

One of the strongest aspects of the proposed national project is that it does not impose predefined solutions. Instead, it identifies 24 critical national issues that require broad consensus. This offers reassurance that the outcomes of the national dialogue will be inclusive, with no one left out. Furthermore, the constitution—proposed to be drafted through a constitutional conference—will be approved via a public referendum. This means that, for the first time in Sudan’s history, the country could have a constitution legitimized by the people rather than imposed by political elites.

In the past, transitional periods have relied on the 1956 Constitution, while constitutional projects during democratic periods often remained incomplete or were shaped by elite conflicts. Under military regimes, constitutions were tailored to fit the ruler’s needs, such as the 1973 Constitution under the May regime and the 1998 Constitution under the Salvation regime. The 2005 Constitution was the only one with broad consensus, but it was not derived from the people; rather, it resulted from a political settlement between the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) and the Salvation regime.

If the national project proceeds as planned, Sudan could, for the first time, have a constitution that has been reviewed and approved by its people before implementation.

The proposed national project still requires further development and continuous discussion across various platforms. Additionally, other initiatives should engage with it—both benefiting from and contributing to it—so that, ultimately, a unified national project can emerge. This is particularly significant as the project’s prospects remain open-ended, with no rigid limitations or exclusions.