The Story of Sudan’s War: Blood in the Nile’s Veins

By: Al-Musallami Al-Bashir Al-Kabbashi

Two years ago, at dawn on April 15, 2023, a war erupted—one that still scorches Sudan—from within its own ranks: the Sudanese Armed Forces clashed with the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), which had once been a part of the military. Every day since, new stories emerge from the heart of this war.

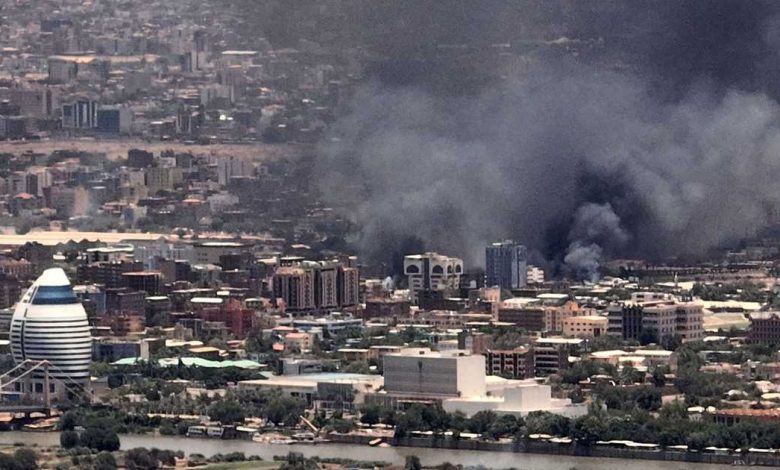

As you enter Sudan’s capital, Khartoum, from its twin city Omdurman via the White Nile Bridge, crossing the meeting point of the Blue and White Nile rivers in the Al-Mogran area, your head spins with the horrors that have unfolded.

This region—once lush and green, a haven for poets, a riverside retreat, and the face of the capital with its soaring towers and dazzling lights—has been reduced to ashes. As if struck by an earthquake in the dead of night, its majestic beauty now lies in ruins: shattered buildings and charred remains.

Venture in any direction from this gateway into Khartoum, and you’re met with evidence of devastation. Beneath each stone lies a story; every path offers a tale to tell. Whether it’s the battles over the Armored Corps, the Central Reserve, the Sports City, the Signal Corps—or the fierce clashes within Al-Mogran itself—each bears its own weight in tragedy.

Ask why Sudan has remained largely unchanged in its sovereign form, untouched by the sweeping redrawing of history’s maps, and the answer dances before your eyes in the story of the Guest House and the Presidential Guard. Fate faced off against fate, and had things played out differently, the course of the nation’s history might have been forever altered.

The battle at the Guest House—the official residence of General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, commander of the Sudanese army and head of the Sovereign Council—is one such tale, one that borders on legend, where wild imagination meets unflinching reality.

Signs of Battle

An anonymous source from the Presidential Guard—the elite force tasked with protecting the president, his residence, and office—recounts how this unit, composed of no more than 400 men and equipped with three tanks and several armored combat vehicles, had prepared for what was to come.

According to military intelligence, RSF had positioned itself at key strategic points across the capital and the regions—an alarming sign. The RSF was slipping out of government control, preparing to seize power.

The Guest House complex, located just south of the army’s General Command, is flanked to the south by the General Intelligence Service and to the east by the Air Force Base. It became the battlefield for one of the war’s fiercest early confrontations. Capturing it would symbolize a decapitation strike—taking down the head of the state.

The Presidential Guard had to hold their ground—400 soldiers, 3 tanks, and a few armored vehicles—against more than 200 RSF combat vehicles, each carrying about seven fighters and equipped with lethal weapons. The RSF surrounded the General Command, including the president’s home.

“On the night before war broke out, Friday night, commanders watched through the control room’s cameras as RSF forces encircled the area,” said the source.

From the south, RSF special units had taken up position in the old National Congress Party headquarters, less than a kilometer away. Nearby was an RSF base, including the residence of RSF leader Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemeti), in the elite Al-Matar neighborhood.

The area was transformed into an RSF garrison, with artillery near the airbase and special forces deployed east of the airport in Al-Safa neighborhood, where they had originally been assigned to secure the airport.

Excavation machinery was also brought in—one placed at the airbase, another near the wall separating Burhan’s and Hemeti’s residences—to breach the barriers and shorten the assault route.

The Zero Hour

“At 8:50 AM on Saturday, April 15, 2023, the first shot rang out near Sports City, south of Khartoum,” the source recounts. Clashes quickly spread to the General Command’s gates—including the Guest House gate.

By 9:10 AM, President Burhan was informed: war had begun, and fighting was already taking place at his doorstep, at point-blank range between his guards and RSF attackers.

RSF forces launched an offensive from the former National Congress site toward the nearby intelligence headquarters, but the Presidential Guard’s tanks repelled a convoy of attacking vehicles and destroyed another coming from Hemeti’s home.

The first day ended with the guards successfully repelling attacks from both the east and south. But the cost was high: 11 guards were killed, one tank was destroyed, and two armored vehicles were lost to Kornet missile fire.

The Course of the War

Day two began at sunrise. RSF snipers had taken up positions in their tower west of the General Command. An order was given to destroy the tower, and a tank opened fire—reducing the tower to rubble, especially its fourth floor, which housed RSF’s DMR communication system.

RSF responded with a three-pronged assault—south, where they had taken the intelligence complex as a base; west, where they attacked the Guest House’s western gate; and east, focusing on Burhan’s residence.

A special mission was launched to reinforce the guards. Colonel Abu Bakr Al-Siryo managed to cross into Khartoum via the Blue Nile Bridge from the north. Though small in number, his unit—elite special forces—was vital.

Wave after wave, the defenders held firm.

On day three, RSF forces led by Abdel Rahim Dagalo (Hemeti’s brother) took control of the Ground Forces headquarters at the western entrance to the General Command. They installed snipers, but a sharp-minded officer maneuvered the last functioning tank into position—after one had been destroyed and the other disabled—dispersing the RSF unit with mortar support before retaking the building.

The assault on the General Command, including the Guest House where Burhan and his deputy Lt. Gen. Shams al-Din Kabashi were located, continued for seven days. When direct assaults failed, RSF imposed a siege that lasted nearly two years.

Inside the compound were thousands of soldiers and top army leadership managing the war through the cracks of the blockade.

The army lost thousands of men within the General Command’s walls—but it never fell. On January 24 of this year, the army finally broke the siege.

With that, RSF’s positions began collapsing, and the army eventually regained full control of Khartoum—except for some pockets in the west and south of Omdurman.

The battles for the General Command—and the Guest House in particular—were not only the fiercest of the war, which exceeded all of Sudan’s previous conflicts in sheer brutality, but also the most politically and strategically significant. Had the RSF succeeded in killing or capturing the president, it would have likely marked the end of Sudan’s constitutional order, regardless of its contested legitimacy. History would have taken a different path—and Sudan, perhaps, would no longer exist as we know it.