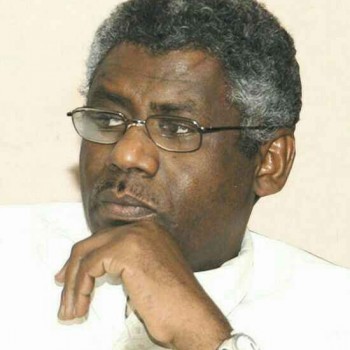

Kamil Idris: An Institutional Mind for an Exceptional Challenge

As I See

By Adil El-Baz

1

Everyone who has taken power in Sudan—from Al-Azhari to Nimeiri, Abboud, Al-Sadiq Al-Mahdi, Al-Dhahabi, Al-Bashir, Al-Burhan, and Hamdok—has repeated the phrase: “We have inherited a heavy legacy.” These words have become a familiar echo in the minds of Sudanese people for decades. But Prime Minister Kamil Idris, who assumed office under extraordinary circumstances, did not repeat this phrase nor complain about the ruin he inherited, even though he took over a torn country, a collapsed economy, a destroyed infrastructure, and a people suffering from displacement, hunger, and the simultaneous threats of invaders, foreign agents, and internal conflicts.

Yet Idris did not resort to complaints. He began his work with a calm and measured speech, relying on his long institutional experience. May God help him.

2

What we need most in Kamil Idris is that institutional mindset he has accumulated through his long journey in the corridors of international organizations. He now faces an existential challenge: to rebuild a state from the ashes—not through slogans, but by reviving institutions that form the foundation of a modern state. Without institutions, all work becomes haphazard, producing no impact and creating no change.

Institutions are not mere administrative ornamentation. They are the foundation of the state—its instruments for ensuring continuity of governance, delivering justice, managing the economy, preserving security, and planning for the future. There can be no stability without institutions, no justice without institutions, and no development without institutions.

3

Kamil Idris is qualified to build state institutions—not only through his academic credentials but also through the practical experience he gained in strict international environments that tolerate no improvisation.

The institutions we speak of today are not merely facing regulatory issues or lacking in competencies. They are in a state of total collapse that cannot be repaired with mere patchwork; they require a complete rebuild from the ground up. Fortunately, these institutions—as organizational structures—are still enshrined in the amended 2025 Constitutional Document. But the issue lies not in their existence on paper, but in their competence, effectiveness, independence, and integrity.

Too many institutions have become hollow shells, useless apparatuses that remain idle because they’ve been emptied of meaning and turned into tools of favoritism and cronyism.

4

Institution-building is not an administrative luxury—it is a matter of existential necessity. Institutions are what transform a fragile entity into an effective one. They regulate the relationship between the state and society, protect the state from chaos, stimulate growth and investment, ensure justice and equal opportunity, and provide the stability needed to implement public policy—regardless of who is in power.

People come and go, but institutions remain. A state built around individuals collapses when they are gone, but a state built on institutions is the only one capable of overcoming crises and rising from setbacks.

5

In his book “State-Building: Governance and World Order in the 21st Century” (2004), American philosopher Francis Fukuyama presents a deep vision that reinforces this truth.

Fukuyama argues that the world’s problem is not a lack of democracy or free markets, but weak states and their failure to build effective institutions.

He affirms that the 21st century requires not only democratic states but also states capable of performing their core functions: ensuring security, enforcing the law, delivering public services, and combating corruption—regardless of the political or economic system in place.

He cites real-life examples of countries that rose from the rubble because they began with building institutions:

Germany, after its defeat in World War II and its division, didn’t start with slogans but established an independent constitutional court, a strong central bank, and a federal system that reduced centralized power.

Rwanda, after the genocide, created “Gacaca” courts to achieve justice and reconciliation, reformed its security apparatus, and focused on professionalism and anti-corruption.

Singapore, which started from scratch after its independence in 1965, emphasized merit and competence, established a high-performing bureaucracy, made the judiciary independent, and fought corruption rigorously.

6

All these experiences confirm that state-building starts with institution-building. No national project can succeed unless it is built on independent and effective institutions. Sudan is fortunate today to have a man with an institutional mind and a professional track record at the head of its government—giving us hope that Kamil Idris might be the one to start from the right foundation. Nations are not built through speeches—they are built through institutions.

7

The greatest achievement Prime Minister Kamil Idris could accomplish is laying the cornerstone for effective institutions—ones that arise from the needs of the nation, not from the whims of politicians, and are run by professional competencies, not political appeasement.

Only then will the project of building an independent and prosperous state become possible.

The exceptional challenge facing the Prime Minister is this: How do we reach that long-awaited state? A state of institutions?

In a country overrun by chaos, conflict, and wars—and by elites ever seeking guidance, yet always boarding the trains of misguidance.