The Nation Is Not a Self-Portrait: In Defense of Satti as Foreign Minister

As I See

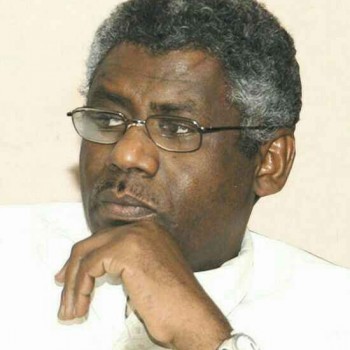

Adil El-Baz

1.

The gravest danger we face today is the tendency of each group to mold the nation in its own image, seeing nothing beyond the horizon but the ghost of their own imagination. The “Belabasah” (those in uniform) are mistaken if they believe they can shape the country according to their vision, just as the “Qahtists” (civilian revolutionaries) erred when they tried to do the same. For them, the nation—past and future—is themselves and no one else. Only they can define its present and shape its future. No one else has the right to step in. They alone see their reflection in the nation’s mirror.

All of them sing praises of a diverse country… a land of millet and thobes and whatever else—but once they seize power through coups, revolutions, or sheer manipulation, their eyes go blind to this diverse homeland. Power becomes a matter of “I alone see the truth, and I will show you only what I see.” Then begins the old melody of exclusion: “That one’s a communist—crush him!”, “This one’s an Islamist—smash him!”, “This one’s a Qahtist—let’s just get rid of him!”

Seriously, what is this?

Many before them have walked this path of delusion, thinking they could tailor the country to their size. What was the outcome? In all cases, the people’s response was one and the same—and it was profound.

2.

The policy of “flooding the system” pursued by the Qahtists is the same as the “lockdown” strategy now brandished by the Belabasah. Both are exclusionary; two sides of the same coin. No difference between them. Both are harmful to the nation’s health and vitality. We’ve seen the catastrophic consequences with our own eyes. Yet we do not repent to God, nor do we apologize to our people for our mistakes and poor judgment. We neither abandon the great wrongs we committed against our country nor overlook the smaller ones for its sake. Thus, we continue to spin in a closed loop, with no horizon for a future we could build together.

3.

Why this introduction? As a reminder—if reminders still benefit Sudanese minds.

Yesterday, news leaked that Prime Minister Dr. Kamal Idris had nominated Mr. Nour Eldin Satti as Minister of Foreign Affairs. Social media ignited, and the usual chorus of accusations began, chanted by those who believe they alone hold the keys to truth.

Why all this uproar? Because Satti is a Qahtist? Suppose that’s true—so what? This “Qahtist” agreed to return home to serve his country under its legitimate leadership.

So what’s your problem? Why close the doors of repentance and block the path of return? Who are you to pass judgment—and by what right?

4.

Suppose Haj Waraq, Yasser Arman, Al-Degeir, or even Khalid Youssef landed at dawn in Port Sudan and said: “We’ve come to serve our homeland under its legitimate leadership.”

Shouldn’t we say to them, “Welcome, enter in peace and safety”?

Wouldn’t that be better than saying, “No way, the doors of this country are closed—it belongs to us, the Belabasah, and no one else”?

How strange is that stance! To what logic does it belong? Politics? Or something we’ve yet to learn?

5.

If we can accept those who took up arms against the state—like Kikel and his companions—and just yesterday the Commander-in-Chief granted amnesty to rebels who surrendered to the Fifth Division in Damazin…

If we applauded that—then why do we now cross our arms and refuse to shake hands with someone returning home in peace and repentance?

How do we shake hands with those who carried weapons, and turn our backs on those who extended their hand in peace?

What kind of judgment is this?

6.

Nour Eldin Satti—I know him personally. We’ve had public disagreements and debates over national issues, when I believed his positions were wrong. But Satti is known as a polite, decent, and highly aware man.

He is currently the most qualified person for the position of Foreign Minister.

He can serve effectively and bring dignity to the role in service of the nation.

He was an ambassador decades ago in multiple countries, including serving as Sudan’s ambassador to the U.S. after the revolution.

He has wide-ranging international and African connections due to his former positions.

He is a professional diplomat, having worked as Deputy Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General in peacekeeping missions in countries like Burundi, Congo, and Rwanda (2002–2006).

He holds a PhD in literature from the Sorbonne (1974), and speaks three languages: Arabic, English, and French.

He has an extensive regional and international network that earned him decorations from France and the Vatican.

Today, he is a member of the Sudan Working Group at the Wilson Center.

His full biography is readily available online—a rich and admirable record.

All of it affirms that he is qualified and deserving of the position.

7.

One of the most important things the Prime Minister can do now is to choose competence—regardless of background: Communist, Islamist, Qahtist, Belabsi, or even a “Red Demon”—it doesn’t matter, as long as they are serving the nation today under its leadership.

To imprison the nation in the cells of our grudges and claim that our love for it gives us the right to exile others—that is a delusion we must discard.

8.

Mr. Prime Minister…

If Satti came to you offering his service to the nation—or if you invited him and he accepted—then don’t look back.

Take him to your side. He is worthy of the position.

Your approach is sound—it is, in fact, the way out for the country we all desire:

A nation that includes us all, where people advance based on competence, not lineage, not party, not uniform.

Whoever wants something else should look for another homeland.

This is a beautiful, forgiving country—one that does not ask about the color of your uniform or past allegiances.

It only asks about your competence and your loyalty—today.

A country full of grace and beauty, full of songs, love, and longing.

Mr. Prime Minister…

Put your trust in God.

Welcome, Satti, as Minister of Foreign Affairs.