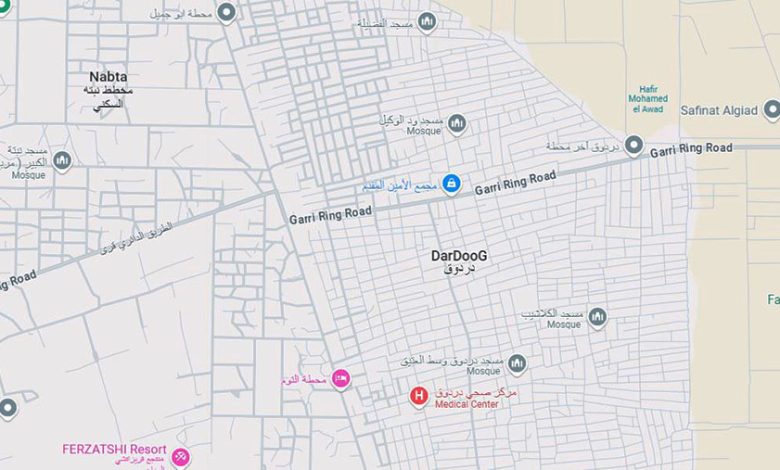

The Customary Constitution and the Local Community Government of Dardok

Sudan Events – Agencies

In Dardok—a region where we currently reside after our internal displacement—and its surrounding areas that have experienced relative calm, night patrols of local citizens have spread. These patrols aim to protect property, honor, and civilian assets, as well as to maintain the safety of homes and ensure the streets are secure for residents. This grassroots initiative emerged as a natural response to the security vacuum caused by the war, after police forces withdrew from public safety roles to join the frontlines alongside the army.

Over time, these patrols evolved to provide various services as part of what could be called a “collective community mindset.” Since nature abhors a vacuum, it became necessary to take practical steps to restore some semblance of normal life—even if through customary laws that maintain social peace and regulate relations among citizens within their local communities.

These patrols contributed to establishing relative security and played an important role in safeguarding markets, ensuring the arrival of food supplies to local shops, and maintaining the flow of goods. Through this communal initiative, local populations managed to fill the executive gap left by the absence of the state, overcoming numerous challenges and hardships. Their efforts alleviated some of the hardships of life under fire and opened new avenues for collective thinking around forming community committees to address civil needs.

These local solidarity efforts developed into service committees, including an electricity committee that took on the task of handling minor outages and downed power lines not related to the main grid. This was done by drawing on the expertise of local electricians familiar with the layout of the network and transformers. The committee collected donations from residents by activating principles of social solidarity, using the funds to pay workers and purchase necessary spare parts.

Electricity was the top priority for this “community government” due to its direct impact on people’s lives under such complex conditions. The availability of power meant bakeries could continue operating without resorting to black market fuel for generators. It also allowed families to store food in refrigerators, reducing daily expenses and easing the cost of living under extraordinary circumstances.

Electricity access also enabled the operation of three artesian wells that had been built through community effort before the war. These wells supplied water through the main and sub-networks of the area, sparing residents from the water crises experienced in other regions.

The community committees multiplied and diversified. A committee was formed to oversee the main market, monitoring the movement of goods and regulating prices through enforcement of customary law, which gradually evolved into a local constitution with rules and regulations stemming from it. The committee built relationships with pharmacists to encourage them to keep their shops open as long as possible and assisted them in sourcing medicines—especially life-saving ones—through difficult routes leading to safer towns. They also encouraged health centers to continue providing services, with some medical staff treating emergency cases in their homes outside of working hours.

One of the most notable achievements of this “community government” was the opening of several takayas (communal kitchens) to provide meals for vulnerable families. These efforts were supported by members of the diaspora from the region, both in Gulf countries and the West. This support also helped fund electricity and water services, health centers, private clinics, and pharmacies.

The local community government, through its customary laws grounded in popular consensus, has proven that people naturally yearn for peace and security—and that through mutual support and collective action, they are capable of rebuilding elements of civil life even in the absence of the state.