A Night with Nadima Mashghoul…

As I See

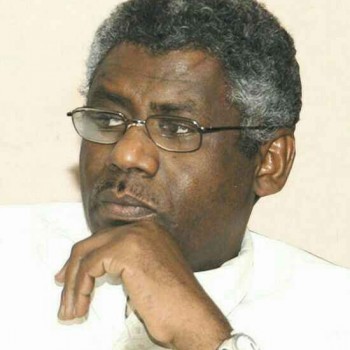

Adil El-Baz

1

(Nadima Mashghoul was present that evening, a queen on her high seat from which she could observe the activity of her café without having to bend forward. She wore her red blouse with orange-embroidered edges. In truth, Nadima Mashghoul was generous in everything—her luscious laughter she shared with all, her speech poured out unreservedly, and she was generous even in her debauchery. In a public poll conducted by trend lovers to identify the most frivolous yet beloved woman in the city, conducted right in her café, she was unanimously crowned the sweetheart of every heart.)

The café of Nadima Mashghoul—crafted by the storyteller Amir Tag Elsir in his captivating novel The Copt’s Tensions—was a hub of news and shady deals. That evening, the café buzzed with whispers and rumors swirled in every corner. Patrons whispered about an impending catastrophe that was bound to strike the country, and that “Al-Mutqaa,” who had appeared in the village of “Abakheet,” was threatening to annihilate and enslave the cities. This, perhaps, explained Nadima Mashghoul’s foul mood that night.

News of Al-Mutqaa and his rebellious army had spread throughout the land, especially after dozens from the city—and even some of Nadima’s café boys—had defected to him.

2

After that night, the events of the novel took on a surreal turn. Al-Mutqaa, the leader of the revolution and author of the Abakheet manifesto, was no longer a rumor. He was now besieging Nadima Mashghoul’s city, shattering her hopes for stability. Amidst the chaos, Nadima married Bakbashi Sabeer—a man the narrator described as: (She married a man harboring thirty chronic diseases that raged within his body).

The novel did not take long to reveal what had occurred in the village after Al-Mutqaa’s men stormed it. The tragedies and disasters that befell the village were but a microcosm of what the entire country suffered due to Al-Mutqaa’s revolution.

3

Nadima Mashghoul, her café, and its patrons were merely a model of the state of decay, corruption, and societal breakdown that had engulfed the nation—where all values had been squandered.

When Amir Tag Elsir contrasts this degenerative condition with the killings, torture, and chaos that followed Al-Mutqaa’s revolution, he paints Nadima Mashghoul’s era—her café and her debauchery—as a rose-tinted golden age by comparison.

4

The symbolism employed by Amir Tag Elsir through his engaging narrative structure did not manage to conceal the historical underpinnings of the novel. It would not be difficult for any Sudanese reader to detect its intimate connection to a specific historical period—despite the author’s denial that the novel is based on actual history.

I do not understand why Amir Tag Elsir tried to distance the novel from its historical roots, even though he drew on real events and effectively rewrote history through fiction—an entirely legitimate literary act.

Strangely, the previous year’s International Prize for Arabic Fiction (Booker), awarded to Youssef Ziedan for his novel Azazel, was entirely grounded in the history of Christianity.

5

The narrator—whose Coptic protagonist, Mikha’il, recounts events in which he is both a witness and central figure—uses an enjoyable storytelling technique to reveal how the post-revolutionary world was constructed and how it began to unravel. He exposes the squandered values that Al-Mutqaa had dedicated his life to restoring.

Amir depicted both the dream-like atmosphere before the revolution and the tragic aftermath in striking contrast. But the dreams of revolutionaries and the harsh truths of reality are worlds apart.

Amir Tag Elsir masterfully wove in small, dazzling stories of many characters, infusing the novel with vivid life through minor but highly compelling roles. Characters like Bakbashi Sabeer, Mikha’il’s beloved Halima, and the poet all contributed richly to the text, despite their peripheral presence.

6

The surrealist style used in crafting this mesmerizing novel (The Copt’s Tensions) did not emerge from it alone, but developed amid Amir Tag Elsir’s vast literary production. We’ve seen this same delightful approach in The Fire of the Zaghareet and The Bride Price of the Cry, among others.

Amir Tag Elsir’s literary project is ascending in a unique form within the Arab novelistic scene, introducing itself to the world with a distinctive narrative style and a voice that is unmistakably his own.