Political Dengue Fever

As I See

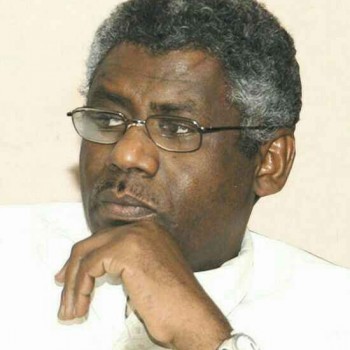

Adel El-Baz

1

Just as epidemics weaken bodies, misleading rhetoric exhausts minds and societies, dragging them into a spiral no less dangerous than viral contagion.

2

The dengue fever currently afflicting Sudanese citizens in Khartoum is a viral infection transmitted by a specific type of mosquito, Aedes aegypti—the same vector responsible for Zika and yellow fever.

There is no antiviral treatment. Transmission occurs through the bite of an infected mosquito that has fed on the blood of a sick person. The only remedy: eliminate the mosquito itself.

3

Yet the “political dengue fever” infecting many Sudanese at home and abroad is far more dangerous than the viral disease, for it spreads through “empty talk”—a threat worse than the buzzing of mosquitoes. Social media platforms and foreign-funded satellite channels have become the new insects transmitting this political epidemic, and they are much harder to eradicate.

No cure has yet been found for political dengue. The only available treatment is quarantine: isolating the online and satellite “creatures” that spread this empty rhetoric, the primary cause of the outbreak.

4

If the symptoms of viral dengue are:

sudden high fever,

severe joint and muscle pain (sometimes called “bone-breaking fever”),

nausea or vomiting,

then political dengue fever presents five unmistakable symptoms—no laboratory test required:

A. Blind hatred of Islamists. The patient trembles within two sentences, then rapidly progresses to convulsions, delirium, and finally a coma in which Islamists are blamed for every catastrophe on earth.

B. Equating the national army with militias. Mention that a militia has rebelled against the military institution, and the patient immediately retorts: “Who fired the first shot?” Inevitably, Islamists are dragged into the discussion. Remind him that one of the revolution’s slogans was “The Janjaweed must be dissolved”—not “The army must be dissolved”—and he falls silent, staring blankly into space, mumbling nonsense.

C. Delirium over foreign support. Whenever the “Triangle of Criminals” (Sumood, Tasis, and the militia) is mentioned, denial sets in. They deny their links to one another, to the militia, and to their backers. The symptoms are the same: fever, eye pain, joint aches. Listeners, in turn, suffer nausea and vomiting.

D. Obsession with power. Patients with political dengue will do anything to cling to power—or to regain it. We have seen them polish the boots of generals, praising them as “heroes” and “skilled leaders.” Yet when those same boots kick them aside, they cry betrayal and cowardice.

E. Endless barking. These patients bark at the mere mention of Islamists, the army, or whenever the people chant “One nation, one army.” They bark whenever the homeland achieves a military, political, or economic victory. On the margins, professional liars—the “drummers”—occupy the corners of cyberspace, barking at anyone approaching their militia patrons and foreign sponsors. Today, they bark everywhere: on TV, on social media, in the streets, and in the press. Soon, they will be left barking only at themselves—once the militia and its backers are decisively defeated.

5

Just as viral dengue recedes with proper health measures, political dengue will only end with the triumph of truth over deception—and the unmasking of agents before the people’s awareness.