In Qabqaba: The Gold That Changed the Course of the Floods

Sudan Events – Agencies

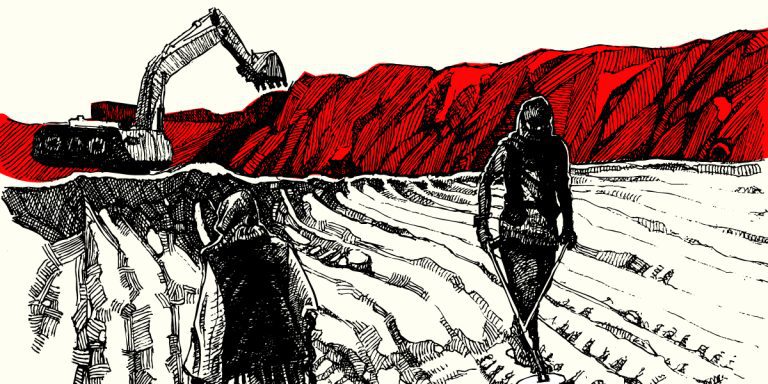

In the autumn of 2024, the infrastructure of the city of Abu Hamed, in Sudan’s River Nile State, was severely damaged by heavy rainfall and flash floods. This occurred despite warnings from the Sudanese Meteorological Authority’s Early Warning Unit, which had classified the danger level as “extreme.” Local organizations reported the collapse of 24,104 homes and 150 service facilities. Yet nature alone was not to blame—the widespread effects of mining activities had altered the flow of valleys and streams, reshaping the region’s topography.

North of Abu Hamed lies Wadi Qabqaba, about 85 kilometers away—a semi-desert plateau interspersed with mountain ranges and rocky hills. Despite its rugged terrain, the area is rich in gold, making it a center for extraction and production since the Meroitic civilization. Qabqaba sits along the Keraf Fault Zone, which extends to the Egyptian border.

Today, Qabqaba is one of Sudan’s largest and richest gold-mining regions. Mining there is not limited to corporate operations but also includes artisanal or “traditional” mining, which began in 2008 and expanded rapidly after South Sudan’s secession in 2011—an event that cost Sudan more than 90% of its oil revenue and triggered a prolonged economic crisis. As the Sudanese pound collapsed and insecurity spread during the ongoing war, waves of internal migration brought thousands seeking fortune in the desert goldfields.

Between 1999 and 2001, joint geological surveys conducted by the French Bureau of Geological and Mining Research and Sudan’s Geological Research Authority confirmed the presence of significant gold deposits across the region.

Beyond the Glitter

In 2008, Morocco’s Managem Group and its Chinese partner Noryang Mining signed an agreement with Sudan’s Ministry of Minerals, granting them an exploration license covering nearly 14,000 square kilometers in River Nile State. Intensive exploration revealed rich gold reserves.

In 2012, Managem established a production unit operated by its subsidiary Manub, and continued discoveries led to the construction of a modern processing plant that, according to the company, complies with international environmental and social standards.

In 2021, Managem acquired 65% of Qabqaba’s expansion projects after a deal with China’s Wanbao Mining. The $250 million expansion was expected to raise annual production capacity to 200,000 ounces of gold.

Field sources confirmed to Atar that Manub—Managem’s operating name—is the main concession holder at Qabqaba, operating two processing plants. Several subcontractors work under its umbrella, including Dal Mining Company, which handles ore transport and operations. Dal operates east of the valley, while Sandra Mining operates in the west. Around them, dozens of companies process mining waste, building large earth berms that have altered the natural flow of wadis and runoff channels. Managem itself fenced its concession zone with earthen barriers dug around its mines and facilities, expanding the site again in 2021.

Following that expansion, massive protests erupted in October 2021—shortly before the October 25 coup—when some 3,000 artisanal miners gathered at Qabqaba’s milling market, torching an administrative office and a tax tent, and attempting to storm Managem’s headquarters in Abu Hamed. Police fired tear gas and live rounds into the air, injuring six people, one of whom was later transferred to Khartoum. The Interior Ministry then deployed joint forces—police, army, Rapid Support Forces, and intelligence—to restore order.

As Manub and its subcontractors expanded, artisanal mining grew even faster. Studies indicate that artisanal mining areas along the Nile expanded from 50 hectares in 2016 to 125 hectares by 2024.

Without regulation, thousands of miners use rudimentary tools and smuggled dynamite to dig pits, despite Sudan’s Defense Industries System holding the only legal authority to supply explosives through its “Target” company. Many of these materials are trafficked to artisanal miners illegally.

A Barren Land

In the 2024 rainy season, environmental and health conditions in Qabqaba and Abu Hamed deteriorated sharply due to pollution from mercury and cyanide used in gold processing, compounded by poor healthcare services. Outbreaks of mining-related diseases and livestock losses were reported.

Protests and sit-ins erupted across nearby towns—Fatuwar and Al-Joul (2020), Al-Abidiya and Al-Sulaimaniya (2022), and Hilla Younis (2025)—condemning the use of toxic chemicals. Residents voiced anger over environmental destruction, while human rights reports highlighted links between some mining firms and Sudan’s military institutions, intensifying public outrage.

Locals told Atar that diseases such as blood disorders, fetal deformities, miscarriages, and kidney failure have surged—symptoms they attribute to mercury contamination despite Sudan’s ratification of the Minamata Convention. They also reported that flood paths have shifted in recent years, damaging infrastructure and property amid official silence.

Efforts by Atar to contact local and federal authorities for comment—including the Abu Hamed locality executive, the Ministry of Minerals’ contracts department, and corporate environment officers—received no response.

A previous Atar report after the 2024 floods noted that mining areas lie above the city’s water distribution lines, and that excavation has altered natural drainage. Milling sites and new settlements now block traditional water routes, redirecting floods and forming new basins across the city.

Mining in the Floodways

Geographer and GIS specialist Haider Fadlallah explained that gold in Qabqaba occurs both as alluvial deposits and within bedrock. Mining, he said, directly and indirectly affects flood channels through soil erosion, open pits, and tailings mounds that reduce water absorption and raise riverbeds—making floods more likely and severe.

Researcher Mohamed Salah Abdelrahman noted that the area between the Red Sea and the Nile has been a gold-mining zone since Pharaonic times. The region now hosts Sudan’s highest gold output and labor concentration. He added that topographic change results from operations conducted directly in flood channels, accumulation of waste, and dense use of machinery—alongside artisanal sieving pits (“garabil”) spread across wadis since 2015. These pits exacerbate runoff and create floods in previously unaffected areas.

Reports confirm that massive excavation and tailing heaps have physically diverted flood routes in Wadi Qabqaba. Gold has long been a pillar of Sudan’s economy—from the pre-revolution government’s budgets to current wartime financing by rival armed groups.

Environmental researcher and writer Sari Naqd emphasized that the uncontrolled boom in gold extraction over the past decade has generated vast amounts of chemically contaminated soil. Unfilled mining pits, he warned, will inevitably redirect floodwaters, while oversight bodies remain absent.

Studies Required but Rarely Enforced

A source at the Sudanese Mineral Resources Company (SMRC) told Atar that each licensed company must conduct an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) before production and receive approval from the Higher Council for Environment. The studies identify waste disposal sites and require companies to rehabilitate land or establish green spaces after extraction.

However, the source admitted: “No company has ever implemented these obligations.”

SMRC has since created specialized firms to treat mercury-contaminated artisanal waste. But illegal use of dynamite persists. “Sudan has over five million artisanal miners,” the source said. “They cannot be stopped under current economic conditions, and many now use smuggled explosives.”

The source added that before each rainy season, the company issues circulars urging firms to take preventive measures against floods and climate impacts. Yet without an effective emergency response center, Naqd warns, future disasters could be far worse than those already witnessed.

Accusations Against Artisanal Mining

Officials insist that the 2024–2025 floods occurred far from company concessions, blaming artisanal mining for changing flood routes. GIS analyses, they claim, show that Manub’s site sits on higher ground sloping north toward Egypt.

But miners like Mohamed Al-Mahdi tell another story: artisanal diggers, using both small and heavy machinery, operate in and around corporate sites with little knowledge of geology or safety. “When the floods come,” he said, “our deep pits fill with water—and sometimes, a thousand miners can be trapped inside.”

The evidence and testimonies gathered in Qabqaba reveal that gold mining is not merely an economic pursuit—it is a pressing environmental and social crisis. As rainfall intensifies under a changing climate, urgent policies are needed to protect local communities and ensure that Sudan’s natural wealth does not become a source of devastation.

Originally published by Atar