Landmarks of the Path to Correction in Sudan

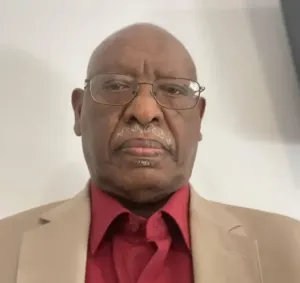

By: Zain Al-Abidin Salih Abd Al-Rahman

The December 2018 Revolution was truly a revolution of the Sudanese street in all its details and currents. It emerged from the neighborhoods of most Sudanese cities and continued for nearly five months to achieve its slogan calling for the fall of the political system in the country—one backed by the Islamic Front. Yet the revolution also toppled along with it the entire traditional political party system in the country, both right and left. This caused the transitional period to stumble due to the weakness of political forces in managing the crisis, as well as the limited political capabilities of their leaders. This weakness opened the door to foreign influence among political actors. Strangely, foreign powers did not intervene to recruit leaders who could serve their agenda; instead, they imposed their own visions on everyone—choosing which leaders should be elevated to the top and which should be sidelined.

The change that occurred in Sudan on April 11, 2019, was a purely political change without a future horizon or political project. The regime fell, and the idea disappeared. Traditional political parties suffered for many reasons. The revolution surprised all parties, leaving the political scene after the fall of the former regime without ideas on how the transitional period should unfold or how the political process should proceed. The Democratic Unionist Party, for example, participated in the former regime with two factions, which held the majority of the party’s grassroots base compared to other unionist currents. These factions were surprised by the revolution and were restricted in movement, being viewed as remnants of the old regime. The Umma Party was paralyzed by internal splits that took away influential leaders who became mere spectators. Imam al-Sadiq also saw his effectiveness decline due to old age, and those around him had limited capability. After his death, internal conflicts worsened, especially since the leadership at the top of the party had limited political experience.

As for the left in its Marxist and nationalist forms:

The Sudanese Communist Party was weakened by the fall of the Soviet Union and the transformations in Eastern Europe. These shifts pushed Khatim Adlan and many leaders to leave the party—leaders who represented the intellectual core driving change. Their departure weakened the party’s intellectual, cultural, and grassroots work. A small group led by Dr. Al-Shafi’ Khidr remained—sharing much of Adlan’s views but preferring to stay and engage intellectually from within—only to be expelled. The party became dominated by a group whose work focused mainly on organization and trade unions, far away from intellectual and mass political engagement. These leaders could maintain the organization but could not produce a political project. Thus the party entered the post-revolution period not knowing what it wanted. The rigidity of the leadership, which merely repeated old texts, was a key reason behind the resignation of Kamal Al-Jazouli from the Political Bureau and Central Committee, choosing instead to remain simply a party member carrying his historical responsibility through his writings.

The Arab Socialist Baath Party also faced major challenges in its political trajectory, beginning with the fall of the Baath regime in Iraq, which had supported the party and offered numerous study opportunities for Sudanese members in Iraqi universities. This was one of the largest recruitment channels. The loss of the pan-Arab leadership, which used to engage in discussions about political work and strategic challenges in different countries, further weakened the party. In addition, the departure of key intellectual figures such as Mohamed Ali Jadin, Abdulaziz Hussein Al-Sawi (Mohamed Bashir), Dr. Bakri Khalil, Prof. Mohamed Shekhon, Prof. Hassan Kamal, and others crippled the party’s intellectual production and impacted its effectiveness.

Looking at other parties that rose to prominence:

The Unionist Gathering was not truly a party but a group attempting to unify various unionist currents. When the Declaration of Freedom and Change emerged, they simply signed onto it and adopted the idea of unionist blocs. Their experience was largely limited to student activism. The Sudanese Congress Party was also a young party, mostly composed of former independent university students. Their experience differed from that of leaders like Mawlana Abd Al-Majid Imam. Additionally, internal conflicts—including the suspension of party members by Omar Al-Degeir and his group near the election period to prevent them from running—had a major negative impact on the party’s performance.

Before the fall of the old regime, there were also conflicts within the ruling National Congress Party that led to the emergence of multiple power centers. There were also Islamist groups outside the regime, such as the Popular Congress Party, as well as younger members who split from it to form the National Movement for Building and Development. The Muslim Brotherhood organization led by Sheikh Al-Sadiq Abdullah Abdul-Majid also experienced splits. All of this meant that the political parties entered the transitional period weak, lacking any clear vision—whether collectively or individually.

Despite the fragmentation of the Islamic Movement into multiple currents, its long experience in ruling for three decades gave it the skills to maneuver and engage in political tactics. It tried to re-enter the political scene through various channels and successfully disrupted its opponents in the Forces of Freedom and Change. These political equations must be studied thoroughly to open pathways for future political currents. Ending the war must be accompanied by a new birth for the political process so that it becomes mature.

We ask God for clarity and sound judgment.