The Anniversary of Sudan’s Independence and the Missing Code

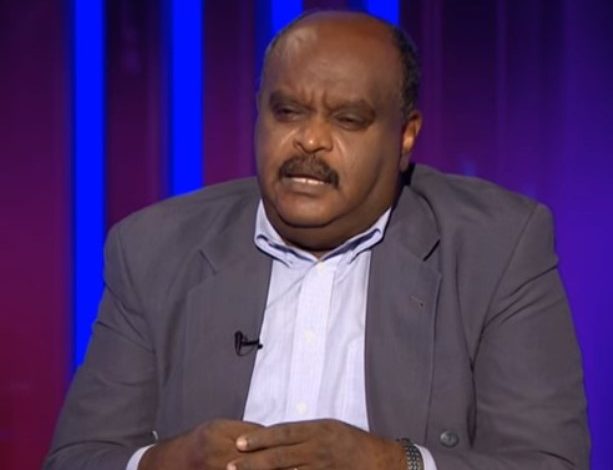

By Dr. Al-Shafie Khidir Saeed

Seven decades ago, Sudan was born holding a document of independence in its hand and the dreams of a nation in its heart. Yet it inherited clearly drawn borders more than it possessed a clear vision for building a state, and it has remained, to this day, hesitant at the threshold of nationhood. At that critical moment, Sudan’s political elite were expected to redirect national energy from resisting colonialism toward answering the foundational questions of state-building through an inclusive national project capable of laying the groundwork for a post-colonial state.

Instead, the elite found themselves immersed in conflicts and competing visions. Politics shifted from a space for constructive dialogue into an arena of clashing wills and narrow ambitions. The question of identity became a platform for conflict rather than a source of cultural richness. Rather than regulating the relationship between religion and the state through a balanced formula that respects faith and personal religiosity while guaranteeing equality among all citizens regardless of belief, religion was transformed by some from a unifying spiritual force into an ideology of confrontation—resulting in the loss of both spirit and state.

The state, which inherited highly centralized administrative structures designed by the colonial power to serve its own interests, failed to reimagine this relationship on the basis of equal citizenship and just distribution of resources and power. The center continued to dominate destinies, while the peripheries felt alienated—until this gap erupted into bloody conflicts and civil wars. Today, on the seventieth anniversary of independence, those foundational questions remain unanswered, and their absence continues to cast heavy and destructive shadows over the country’s unity and national fabric.

What is even more troubling is not merely the failure of political elites, but the transformation of that failure into a permanent political culture—one in which crises and wars became the constant, while peace and stability turned into the exception. For seven decades, the country has been trapped in a vicious cycle: a weak state leads to conflict, and conflict further weakens the state. The first major shock was the secession of the South; the second was the brutal war of April 15; and further shocks lie ahead unless the pace of change accelerates.

Perhaps the deepest tragedy of the Sudanese experience lies not only in poverty or war, but in this persistent and elusive failure of political elites to crack the code of building a modern, stable state. Since independence, Sudan’s ruling elites approached state-building with the mindset of an “owner” rather than a “servant,” governed by the logic of “victor and vanquished.” They reduced the code to a single ideology, imposed one vision of identity while excluding others, embraced a rentier economy that treated national resources as spoils rather than developing them as national capital, and relied on a brutal central authority that believed military and security power to be the sole foundation of stability.

The code for building a modern, stable state is not merely a set of constitutional articles or legal provisions. It is a subtle blend of historical vision, collective will, justice as a founding value, and institutions as living structures infused with trust. It is the ability to transform a “group” into a “society,” and a “society” into a “state.” It is the delicate balance between authority and freedom, unity and diversity, individual interest and the public good. At its core, it is the capacity to turn contradictions into productive diversity and conflicts into a dynamic of construction.

Seventy years of failure should be enough to teach us a harsh lesson—one that some have yet to grasp: states are not built by iron and fire, nor by ideology, but by inclusive ideas, effective management of diversity, and the ability to transcend narrow selves toward the broader horizons of a shared country.

Today, on the seventieth anniversary of its independence, Sudan still stands holding a key it has not learned how to use, and a map whose symbols it has yet to decipher. Yet history is not destiny, and failure to unlock the code of state-building does not mean inevitable loss or despair. This code is not mystical magic; it is an accumulative human experience that can be acquired. The Sudanese people, in their diversity, culture, and resilience, carry the elements of this code deep within them—in the wisdom of the “citizen” in remote rural areas, in the creativity of the “intellectual” in the cities, and in the struggle of “youth” for a better tomorrow.

The Sudanese people’s capacity for revolution and renewal offers hope that a new generation may be better equipped to crack the code—a generation not born under the cloak of old ideologies, one that sees diversity as enrichment rather than threat, and dialogue as a path rather than a weakness. The task of this generation is not to reinvent the wheel, but to rediscover the simple yet profound human code of coexistence: justice as the foundation of authority, freedom as the condition for creativity, and equality as the secret of unity.

This new generation has already begun searching for that code, as reflected in the slogans of the December 2018 revolution—freedom, peace, and justice—and in grassroots initiatives that managed people’s lives amid the absence of the state. These initiatives established self-organized relief networks, mechanisms for civilian protection, and even local mediation efforts to halt fighting. The experience of emergency response rooms, which brought together young people from diverse backgrounds, orientations, and ethnicities, demonstrates that the social fabric has not been completely torn apart, and that Sudanese society remains capable of inventing local solutions for coexistence.

The war of April 15, 2023 erupted as a struggle for power, but its roots extend deep into the contradictions of incomplete independence. It therefore evolved into a multi-layered war: a center–periphery conflict, a war of identities, a war of interest groups and resource plunder, and a proxy war that turned Sudan into an arena for regional and international rivalries—further complicating the crisis and prolonging the conflict.

On the seventieth anniversary of its independence, Sudan stands at a historic crossroads: either the war continues until the Sudanese state disintegrates entirely, or a radical peace process begins—one that builds a new state upon the ruins of an incomplete independence. The first option spells an unimaginable catastrophe. The second is difficult and arduous, but possible—if the will of the Sudanese people converges with a genuine international will for peace, not merely for crisis management.