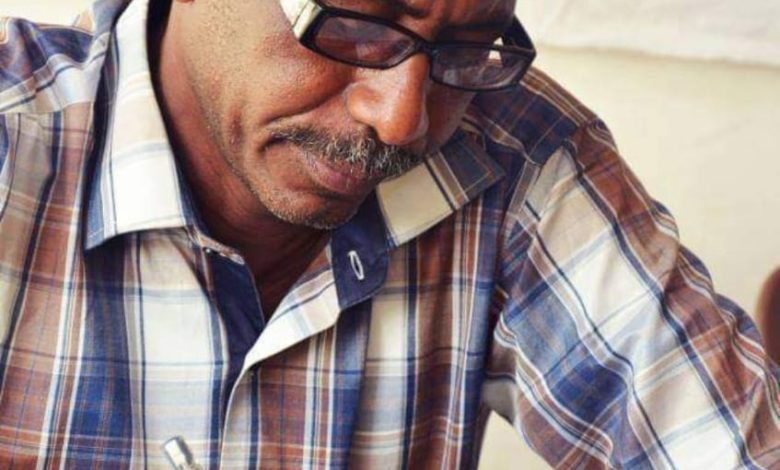

Artist Mustafa Ahmed Al-Khalifa and words about theater

Alsayed Alsir

Since the eighties of the last century, the artist Mustafa Ahmed Al-Khalifa has been considered one of the most prominent actors in the Sudanese theater movement and television and radio drama. He has been able to carve out a distinguished position for himself in the theater industry. He is one of the few authors whose plays have met with great public success, and one of the few authors whose career has continued without interruption. Mustafa, who wrote a number of plays that can be described as “public” plays, because of the great response they received from the audiences of Khartoum and other cities in Sudan, we find that he was unique in a number of characteristics that can be summarized in:

1. What we can call “political theatre.” Most of its plays take the authority and its relationship with the nation and the citizen as their subject.

2. He relied on texts written by other writers and prepared then Sudanize them, noting that he had other plays that he himself had written.

3. His association, especially in his long plays, with one director, Muhammad Naeem Saad, and a specific team of actors, consisting of the Friends Groupe.

4. When compared to those of his generation, we find that his works are the most popular. Plays such as “The Clown,” “Habzalam Bazaza,” “Party on the Stale,” “Statement Number One,” “Dish Malik,” and “The Regime Wants” which is considered Sudanese plays that was shown more than once and received great public response.

From my own position, which is based on knowing Mustafa personally, and following his work, I can say that he was seeking for his theater to have a role in re-posing social questions, and in the ability to create laughter and then “scandal.”

When I say his theatre, I mean this, as some do not see preparation, quotation, or rewriting as a reliable authorship. This is an opinion that will not hold up when looking at the history of theatrical text in the world, as we will find hundreds of theatrical texts that built on previous texts, and the examples here are many. For example, the play (Hamlet Wakes Up Late) by the Syrian Mamdouh Adwan, which was based on the play (Hamlet) by Shakespeare, and the play (Antigone) by the Frenchman Jean Anouil, which was based on the play (Antigone) by Sophocles.

Our artist says: (Theatre/drama is a noble art created by man to create a parallel world in which he deconstructs his life world, and through which he poses those difficult questions. Therefore, in its inception, this art was linked to religion, myths, and great existential questions such as the questions of death, life, and justice. Therefore, it was not strange that the names of great philosophers were mentioned in human history, as they were associated with this art in some way, such as Aristotle. It was also not strange that this influence of theater continued throughout the ages, and it became a human art that all people shared and included in their concerns for change and empowering the culture of goodness, truth, and beauty.

Regarding the importance of the writer being aware of his culture and being haunted by it, he says: (A writer who does not know the culture of his society and the historical moment that his society is experiencing cannot create a theater that addresses people and carries the elements of immortality).

Concerning the Sudanese writer, he says:

(Although Sudan is a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural country, rich in myths, stories and rituals, the Sudanese playwright was only able to express this legacy poorly. This may be due to the dominance of a single view and the absence of pluralism and diversity. Perhaps this is what created an incomplete identity at the theater level. The identity of Sudanese theater in most cases does not deviate much from the identity that the authorities sought to establish, which has lost many opportunities for our theater and writers in drawing from our diverse heritage in myths, stories, anecdotes, history, daily lives and wisdom, and I do not exclude myself, as we have all failed, except for some exceptions. There are very few efforts here and there to make our theater express this linguistic, cultural and religious diversity, so our loss was huge, although I see a glimmer of hope in the possibility of Sudanese theater expanding its identity, speaking in more than one tongue, expressing more than one culture and telling about more than one place and about more facies.

I used to see, and still do, that Mustafa is somewhat different from many theater students in Sudan, and this difference appeared to me in his ability to transform complex theatrical knowledge into work that the viewer interacts with, instead of announcing it for show only, and in his ability to emphasize that any theatrical performance is necessarily public, and there is no theatrical performance that can be said to be non-public.

This article is not complete without referring to our artist’s relationship with the maker of theater audiences in Sudan. The distinguished Professor Saeed, and his influence on him, says in this regard:

(…..But my meeting with the honorable Professor Saeed and working with him as an actor was the fundamental shift that brought me to the theater. With him, I learned about the importance of teamwork in creating theatre, both text and presentation, and the inevitability of theater having an audience, and having a role in issues of enlightenment and criticism.