The Return to Khartoum: Murals Speak, People Narrate

Sudan Events – By Mohammed Elsheikh Hussein

If the poet Ibrahim Al-Abadi has summed up the narratives of life in Omdurman in the past, when he said about his town “its people narrate well, and me I remember Omdurman and its people” the post-war atmosphere that is coming to an end suggests that we should present new ideas on the eve of the expected return to Khartoum.

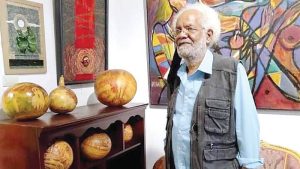

The well-known artist Adil Kubaida is currently seeking to create a new city in Omdurman whose walls are filled with murals that speak to and fill our lives with visual delight that add more dimensions to our dreams and imagination.

Wall painting is not a decorative work, as much as it is an expressive vision in a specific spot that takes us out of the space in which we live. Kubaida’s mural painting is at its best when it achieves a continuation of architectural design, which serves as material for recording daily life.

This is because art displays revelations that do not exist in reality, through which the artist can transform the wall into a picture painting whose components become part of the design and interact with it. In the modern era and with the limited spaces of our homes, wall painting has become an effective element in addressing the narrowness of architectural space.

As for the origin of the idea of the Omdurman mural (Al-Buqaa), it stems from the important role that Omdurman played in formulating a national identity for the people of Sudan and creating a Sudanese culture that plays a pioneering role in the central context of the civilizational dialogue of Sudanese marginal cultures, which according to Kubaida are now in the shadows of modernity and communication technology.

Kubaida seeks to reiterate the history of Omdurman in his murals through serious attempts to complete the cultural dialogue that the city began, characterized by tolerance and respect for others, despite all the distortions caused by the war on its alleys and neighborhoods in the name of civilization.

As for the origin of the idea of the Omdurman mural (Al-Buqaa), it stems from the important role that Omdurman played in formulating a national identity for the people of Sudan and creating a Sudanese culture that plays a pioneering role in the central context of the civilizational dialogue of Sudanese marginal cultures, which according to Kubaida are now in the shadows of modernity and communication technology.

Kubaida seeks to renovate the history of Omdurman in his murals through serious attempts to complete the cultural dialogue that the city began, characterized by tolerance and respect for others, despite all the distortions caused by the war on its alleys and neighborhoods in the name of civilization.

Kubaida draws attention to the fact that architecture first began the change movement, to extract familiarity and tolerance from the hearts of the people of Omdurman. From this point, Kubaida strives to participate through a modernity that carries a tolerant and equal dialogue that enables Omdurman, the city and people, to communicate, to play its role in rooting and strengthening the great identity within scientific and practical frameworks.

In order to dismantle the ambiguity surrounding this gesture, Kubaida points out that the artistic value derives its effectiveness from its connection with citizens and on the walls of their homes. Here, the wall emerges first as a mediator that contributes to shaping the nation’s conscience against alienation. Secondly, the wall stands out as one of the most important visual arts that has had an impact on the recipient throughout history, in addition to its role in shaping the social and political thought of the nation.

He said that the Omdurman murals are a new plastic arts experience that comes within its general context to:

(a) Renewing the dialogue between the contemporary creator and the popular mediator.

(b) Treating spaces in the city of Omdurman in an artistic manner.

(c) Increasing dialogue between the groups and cultures that settled in the city of Omdurman, and transforming the city into an anthropological museum that enables modern people to know their roots and their social, cultural and political history.

(d) Empowering the neighborhood’s youth with their creative tools to formulate a new aesthetic, moral and ethical reality that suits their contemporary culture.

Adil Kubaida said that many visual artists believe that drawing on walls is an important civilizational and cultural tool, and it is largely a tool and a way to communicate with the public, given that it is a daily, direct work that is close to them, as it is not possible to draw away from people’s eyes.

This experience is supported by the fact that the mural is a painting that addresses an ordinary audience that differs in their orientations and level of culture, so the language must be simple and clear.

The artist must use symbols that are easy to understand and deal with without complexity or exaggeration, taking into account that he is addressing a general audience. A mural is the easiest way through which an artist can share with his community and people their concerns and feelings and celebrate with them the occasions that they cherish and are interested in commemorating.

The murals have many features that make them superior to others, and the most important of these features is that they are a work of art in which a number of artists participate. In addition, the average citizen does not need to go to a showroom to see them, as they are located on a public road in a place that is easily accessible.